Peter Jones’s Masterclass – Epidemic print: medical incunabula and their readers – A post by Katie Flanagan (Royal College of Physicians)

I was delighted to get a place on the masterclass “Epidemic print: medical incunabula and their readers”, particularly as I look after the Royal College of Physicians’ rare book collections which includes over 100 incunabula. The session was conducted by Mr Peter Jones, the librarian at King’s College, Cambridge, who certainly brought the books on display to life, as well as putting them into context.

Mr Jones commenced with an overview of how medical incunabula ended up in Cambridge University Library. Many arrived in Cambridge relatively soon after printing, including nine separate volumes brought from Ferrara in 1477 straight to Cambridge. After religious houses, doctors were the main acquirers of books, so medical texts came to Cambridge from the 1470s onwards. These were intended for both medical practice and academic study and many found their way into the University Library. The spread of epidemic disease in Europe played a big part in the production of medical books. In the 15th century plague was localized and specific, so places where the plague struck were also places where plague tracts were produced. Diseases such as the ‘English Sweat’ and syphilis had a high mortality rate even amongst the wealthy and led to the publication of related tracts.

We went on to examine twenty incunabula in detail. One of the joys of a small group such as this, was the chance to see these close-up and study them ourselves. They were arranged in thematic groups, and Mr Jones introduced each one, with plenty of opportunity for further comment and questions from participants.

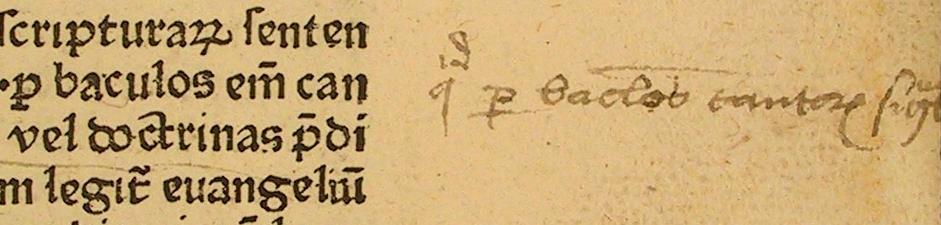

We started off with texts whose publication followed an outbreak of disease, notably the Regimen contra pestilentiam, ca. 1485 (ISTC ij00013400; Inc.5.J.3.5[3604]). These are texts that tend to be ephemeral in nature and are accidental survivors; there were probably far more of these in circulation than we are aware of now. There were two editions of this text in 1485, coinciding with the arrival of the English Sweat. It was a useful comparison with the plague tract at the RCP (ref. no. 21858), extensively annotated and published in Antwerp between December 1486 and May 1487 (ISTC ij00003550). Similarly, the next item, Jacobi Soldi Opus de peste , 1478 (ISTC is00613000; Inc.5.b.10.10[2064]), demonstrated how these texts were written to be used, with annotations dating from the 15th and 16th centuries.

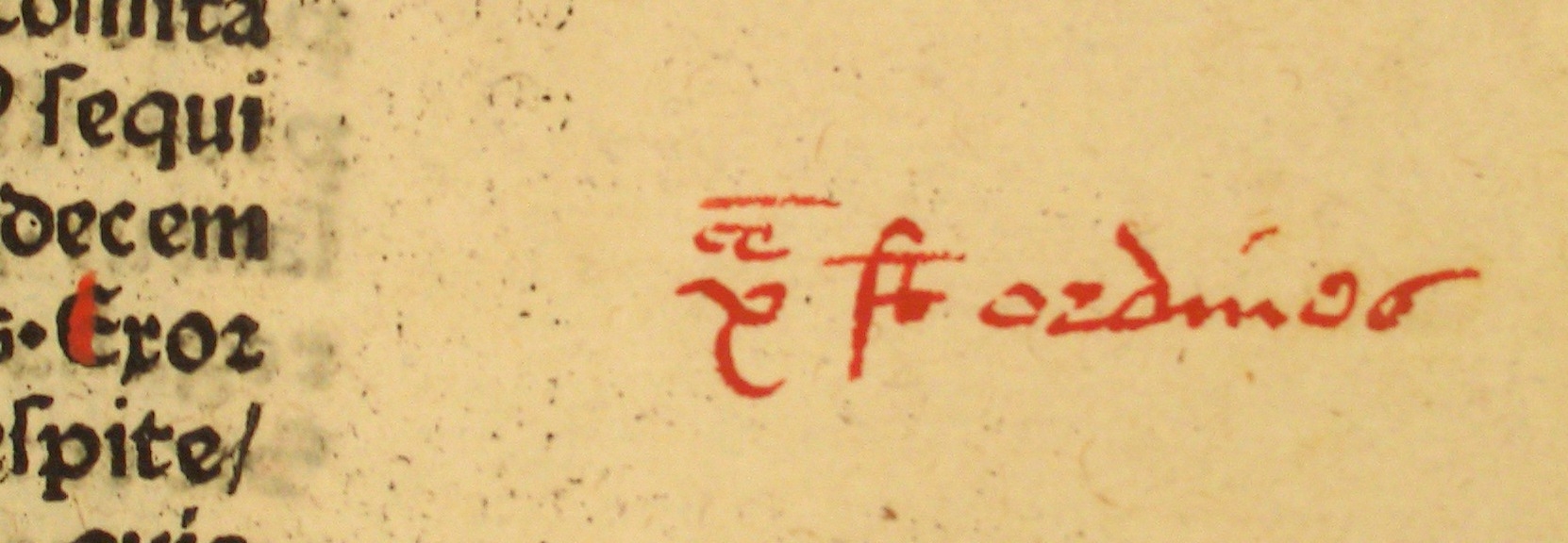

Another example was a broadside, Johann Muntz, Tabula minutionum, before 1495, with tables giving particular months of the year for blood-letting, targeted to provide information with a very practical reference purpose (ISTC im00875300; Inc.Broadside.0[4100]).

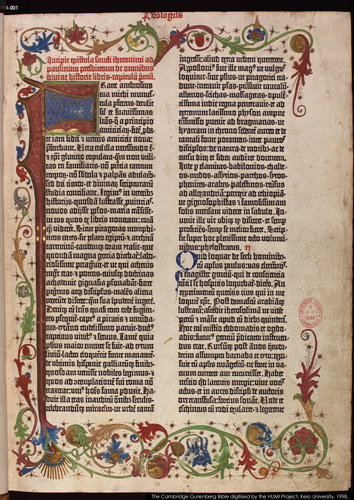

Several questions from the historians in the group were posed about the technicalities of printing illustrations whilst we looked at some herbals. The same woodcuts were used repeatedly, making the herbal of little use in identifying plants. Their use lay in describing use of plants in medicine, rather than botanical description. One example of this was the Herbarius Latinus, 1484 (ISTC ih00062000; Inc.4.A.1.3b[19]), with woodcut hand-coloured illustrations, names given in Latin and German and annotations giving Polish names in addition. These texts tended to be old-fashioned for the time – in two thirds of publications of this time the text was by an author who was already dead, for example, the Hortus sanitatis, not after 21 October 1497 (ISTC ih00487000; CCB.47.62).

Conversely the Opusculum aegritudinum puerorum, 1486-87 (ISTC ir00241000; Inc.5.F.2.7[3380.1-3]) was by a living author, Cornelis Roelans, a town physician. He put together various writings on the diseases of children. Tantalisingly, the first 77 leaves of every known copy of this work are missing, possibly indicating the author was not happy with the proofs and had them all disposed of? The only survival is single leaves found in Cambridge bindings.

Another theme was books without a strictly medical approach. One example was De secretis mulierum, 1485 (ISTC ia00304500; Inc.4.J.3.4[3603]), a book about generation and reproduction, written by an author in a monastic house, and notably misogynistic! This showed a more philosophical approach than scientific. Information about medicine was not only accessed via medical texts, but also via encyclopedias, an example of which was the final book on display, Bartholomaeus Anglicus, De proprietatibus rerum, 1496 (ISTC ib00143000; Inc.3.J.1.2[3559]).

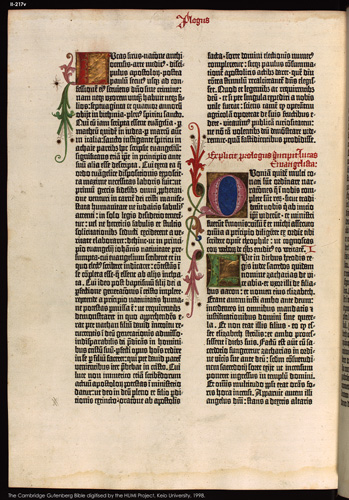

Other highlights for me included seeing another copy of Antonio Gazius, Corona florida medicinae, 1491 (ISTC ig00111000; Inc.2.B.3.45[1506]), of which we also have a copy at the RCP (ref. no. 21416-3), although, sadly, our copy isn’t annotated, and Antonio Guainerio, Practica, 1497/98 (ISTC ig00521000; Inc.3.B.3.85[1671]), which contains medical recipes at the back, attributed to Richard Bartlot, a 16th century President of the RCP.

The masterclass was a great overview of medical incunabula, and, as well as learning about the books themselves, provided a good opportunity to engage with the variety of people involved with studying and working with incunabula, not just librarians. A useful bibliography was also provided. My thanks to Mr Jones, for such a lively and interesting masterclass, and to the staff of the Rare Books Room for organizing the event and putting out the examples for us to view.

![Inc.3.B.3.45[1519], a3v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Inc.3.B.3.451519-a3v-reduced.jpg)

![Flanagan - Inc.5.J.3.5[3604] - Plague tract - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Flanagan-Inc.5.J.3.53604-Plague-tract-reduced.jpg)

![Flanagan - Inc.Broadsides.0[4100] - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Flanagan-Inc.Broadsides.04100-reduced.jpg)

![Flanagan - Inc.4.A.1.3b[19] - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Flanagan-Inc.4.A.1.3b19-reduced.jpg)

![Flanagan - Inc.3.B.3.85[1671] - Bartlat annotations 2 - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Flanagan-Inc.3.B.3.851671-Bartlat-annotations-2-reduced.jpg)

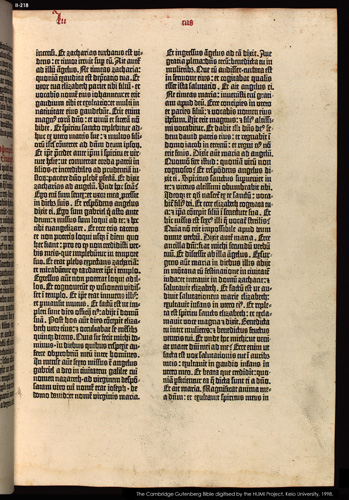

![Inc.1.A.2.3[84], f. [215]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.2.384-f.-215v-reduced3.jpg)

![Inc.1.A.1.1[3761], 2, [y6]v - first mark](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.1.13761-2-y6v-first-mark3.jpg)

![Inc.1.A.2.3[84], f. [215]v - first line](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.2.384-f.-215v-first-line3.jpg)

![Inc.1.A.1.1[3761], 2, [y7]r - second mark](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.1.13761-2-y7r-second-mark3.jpg)

![Inc.1.A.2.3[84], f. [215]v - last line](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.2.384-f.-215v-last-line1.jpg)

![Inc.3.J.1.3[3576], a1, Sarum Missal - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.3.J.1.33576-a1-Sarum-Missal-reduced.jpg)

![Inc.3.J.1.3[3576], Sarum Missal, calendar - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.3.J.1.33576-Sarum-Missal-calendar-reduced.jpg)

![Inc.3.J.1.3[3576], Sarum Missal, explicit - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.3.J.1.33576-Sarum-Missal-explicit-reduced.png) The book’s history during the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is unrecorded. In 1693 it was given by one “Arnold de Wycomb” to George Whitton. Whitton was a graduate of King’s College and native of Wycombe in Buckinghamshire who incorporated at Oxford in the same year he received the book; the unidentified Arnold is presumably a relative or family friend from the same place. The Missal must have passed into the collection of Bishop John Moore shortly after that date and would have reached the library with the remainder of the Bishop’s collection in 1715. It was probably given its rather workaday half-leather binding shortly afterwards.

The book’s history during the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is unrecorded. In 1693 it was given by one “Arnold de Wycomb” to George Whitton. Whitton was a graduate of King’s College and native of Wycombe in Buckinghamshire who incorporated at Oxford in the same year he received the book; the unidentified Arnold is presumably a relative or family friend from the same place. The Missal must have passed into the collection of Bishop John Moore shortly after that date and would have reached the library with the remainder of the Bishop’s collection in 1715. It was probably given its rather workaday half-leather binding shortly afterwards.![Inc.1.A.1.3a[3762], I, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.A.1.3a3762-I-a1r-reduced.jpg)