A sixteenth-century Cambridge provenance for a Belgian incunable?

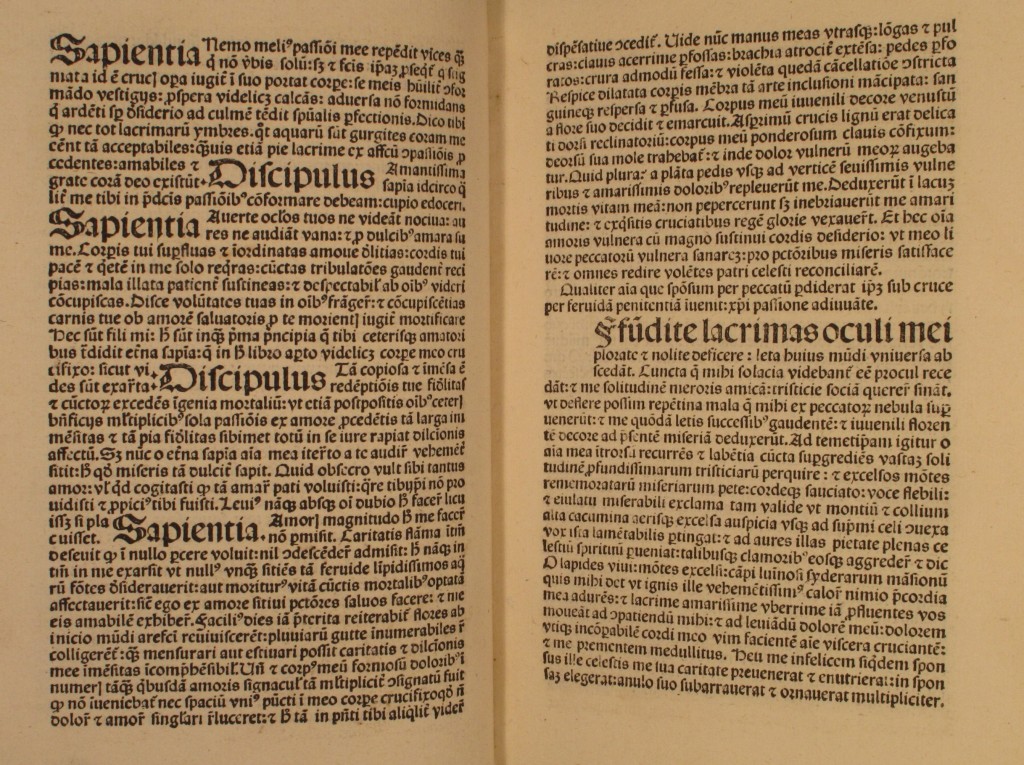

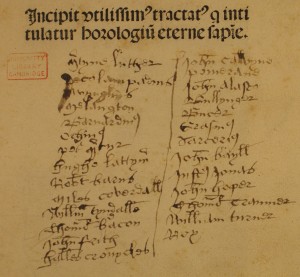

The sixteenth-century list on the first leaf of Henry Suso’s Horologium aeternae sapientiae

(Alost: Thierry Martens [between 1486 & 1492]), Inc.5.F.1.3[3154], ISTC is00874000

Holdsworth bequeathed his huge library (over 10,000 volumes) to the University on two conditions: that the church should be resettled within five years of his death (re-established after the breakdown of authority following the execution of Charles I in 1649), and that the University return Lambeth Palace Library (confiscated by Parliament during the Civil War and given to Cambridge) to the Church. Should either one of these conditions remain unfulfilled the collection was to go to his own college, Emmanuel. By 1654 Emmanuel College could make its claim on the first condition but, after a lengthy dispute, the collection was eventually presented to the University in 1664. Thanks to well-kept library records we know that our copy of the Horologium was once bound with two other works: another printed by Martens (Pomerius’ Prognosticon) c.1487-88, and a life of St Jerome printed by the so-called Printer of the Mensa Philosophica in about 1487. The Horologium is a rare work, with this edition recorded in only two other UK libraries (the British and Bodleian Libraries) in addition to a scattering of copies on the Continent.

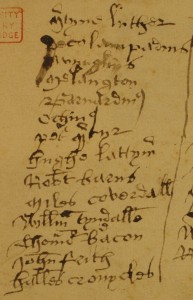

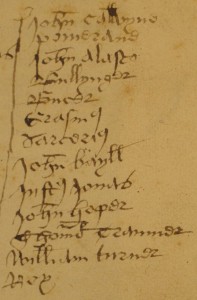

The volume bears few signs of use; it is in early twentieth-century half morocco by Stoakley of Cambridge, and contains no decoration or textual annotations, except for a fascinating list written on the first leaf (for a full transcription see the end of this post). Underneath the two-line title printed at the head of a1r are two columns of names, divided by a vertical line and written in a mid-sixteenth century English hand (pointing to the book’s presence in England at that time). The left-hand column contains 13 entries in 14 lines and the right-hand column 12 entries in 13 lines (the sixth and seventh entries in the right-hand column, ‘Erasm[us]’ and ‘Sarcerius’ are thought to be one entry for the Lutheran theologian Erasmus Sarcerius). Every entry except for that at the bottom of the left-hand column (‘halles cronycles’) is the name of a Reformation author. The presence of ‘halles cronycles’ (The union of the two noble and illustre families of Lancastre and York by Edward Hall, which appeared in 1542) suggests that this could be a book list, possibly compiled by a student or fellow in the University. However, the lack of titles for any of the other names in the list, or any contemporary provenance for the volume is frustrating, and makes dating or localizing the list rather difficult.

Given Holdsworth’s presence in Cambridge from 1607, it is not impossible that he might have purchased it second-hand, either from a bookseller or from one of his contemporaries in the University, and that it had been in the town during middle of the sixteenth century. The nature of the names on the list points to a turbulent time in English history, during which Cambridge played quite an active role. From the early 1520s a group including Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, Robert Barnes, Miles Coverdale, William Tyndale and John Bale (all on the list) met in the White Horse Tavern, which stood on King’s Parade until 1870, to discuss Lutheran ideas and the work of Erasmus (who had been at Queens’ College from 1510 to 1515) at a time when England was still a Catholic country. Such meetings were quite revolutionary, a decade before the break with Rome, and lead to the first openly evangelical sermon in England, preached at St Edward’s Church in Cambridge at Christmas 1525. Other authors on the list, though not connected directly to Cambridge, were exiled in England, including Bernardino Ochino (1487-1564), a convert to Protestantism who sought asylum here with Peter Martyr (who appears below him in the list) during the reign of Edward VI. If indeed this is a book list, it refers presumably to Ochino’s sermons, printed in Italian in Geneva during the early 1540s but translated into English and printed twice in 1548 (in London and Ipswich). Fifth in the right-hand column is Martin Bucer, a Protestant reformer influenced by Luther. His fate rather summarises the changeable nature of religious affairs at this time. He was appointed Regius Professor of Divinity at Cambridge in 1549, during Edward VI’s protestant reign, but a little more than two years after his arrival in England he was dead. He was interred in Great St Mary’s church with great ceremony, but with the arrival of the Catholic Queen Mary in 1553, his remains were removed from the church and burned along with copies of his books. Finally, Elizabeth I brought Protestantism back to England and restored his reputation, with the help of men like Matthew Parker, Master of Corpus Christi College (1544-1553), Vice-Chancellor of the University (1545 and 1548) and Archbishop of Canterbury (1559-1574).

The presence of books in the early University has been studied in great detail by Elisabeth Leedham-Green, in her Books in Cambridge inventories (1986), in which are printed book lists from Tudor and Stuart probate inventories from the Vice-Chancellor’s court in the University. With the increase in the publication of controversial texts from the 1520s onwards, many authors were banned in this country and the possessions of members of the University were searched for heretical books in the reigns of Edward VI and Mary I. This purge may explain why the study records only one work by Ochino (the 1556 edition of his Syncerae et verae doctrinae), one work by Jan Łaski and one copy of Hall’s Chronicles, though all are in the 1589 catalogue of Andrew Perne’s library, by which time such works were not considered to be so dangerous. On the other hand, Bucer is well represented and is recorded as being owned in Cambridge as early as 1535. John Frith is uncommon, represented in only three collections, one as early as 1543, and two authors – Justus Jonas and John Hooper – are unrecorded in her study. Certain individuals had libraries which contained many books of a reforming nature, including Dr James Townley, who took his BA in 1521/22 and doctorate in 1538. He was a Fellow of Queens’ College from 1523 until 1528, and of Christ’s 1532-1539, and the list of his books compiled after his death in 1543 (reproduced in Leedham-Green’s study) records 77 titles. Among these books we find many of the authors on our list, including individual works by Luther, Tyndale and Frith, two works by Bugenhagen, three each by Bucer, Melancthon and Zwingli, four by Erasmus Sarcerius and no fewer than nine by Erasmus – hardly surprising given his influence in Cambridge and further afield at this time.

With this in mind, it is fascinating that every name on our list was banned at some point or another. Tyndale had been banned as early as the summer of 1530, and in July 1546 it was made illegal to possess any works by Frith, Roy, Becon, Bale, Barnes, Coverdale and Turner. In June 1555, under Queen Mary, all those forbidden previously, in addition to Luther, Oecolampadius, Zwingli, Calvin, Bugenhagen, Alasco, Bullinger, Bucer, Melancthon, Ochinus, Sarcerius, Peter Martyr, Latimer, Jonas, Hooper, Cranmer and – crucially – Hall’s Chronicles, were also outlawed. With this knowledge, it is possible that our list was either compiled either by a very imprudent member of the University seeking reading material, or (as seems more likely) by someone responsible for seeking out illegal works in the University (any thoughts readers may have are welcomed). Whatever the reason for its compilation, it symbolises Cambridge and its University as a melting-pot of ideas during this troubled period.

Transcription of left-hand column

- M[ar]tyne luther

- Oecolampadius

- Zwynglius

- Melangton

- Barnardin[us] ochin[us] [split over two lines]

- Pet[rus] m[art]yr

- Hughe lattym[er]

- Rob[er]t barns

- Miles coverdall

- Wyll[ya]m tyndalle

- Thom[a]s bacon (i.e. Becon)

- John frith

- Halles cronycles

Transcription of right-hand column

- John calvyne

- Pomerane [Johannes Bugenhagen]

- John Alasco [John Łaski]

- Bullynger

- Bucer

- Erasmus Sarcerius [split over two lines]

- John bayll

- Just[us] jonas

- John hooper

- Thom[a]s cranmer

- William turner

- Roy [presumably William Roy, who assisted Tyndale with his Biblical translation in Germany; possibly his Brefe dialoge bitwene a Christen father and his stobborne sone, translated from the German of Wolfgang Capito and published in 1527]

My thanks to Dr Elisabeth Leedham-Green (Archivist & Deputy Praelector at Darwin College) for her assistance in deciphering some entries in the list and discussing with me the possible dual meaning of the entry ‘Erasmus Sarcerius’