Inspired by David McKitterick’s recent Masterclass exploring some of the ways in which the make-up of books can be changed once they leave the printer, an erroneous quire within a recently catalogued copy of Durand’s Rationale divinorum officiorum ([Basel: Michael Wenssler, not after 17 Mar. 1476] – ISTC id00411000) raises some interesting questions about the book’s production history and its later use, but frustratingly answers none.

Inc.1.C.1.2[2286] has a significant Cambridge provenance. The book appears in a manuscript list of early donations to the Library (MSS Oo.7.52), listed as item 72 ‘Ex dono Reverendi Patris in Xto Thomæ Rotherami Episcopi Lincolniensis et Cancellarii Angliæ’. The list was compiled in about 1658 by Jonathan Pindar, Under Library-keeper, and in the words of J.T.C. Oates “Its accuracy has long been suspect”.[1]

Thomas Rotherham (1423-1500), Archbishop of York and Chancellor of England, was also Chancellor of Cambridge University in 1469 and at intervals (perhaps continuously) from 1473 to 1492. In 1475 he was listed amongst the University’s principal benefactors for his contribution towards the completion of the east front of the schools, which included the Bibliotheca minor, for which he had provided the furnishings and a donation of books. This original gift was supplemented with other books during his lifetime, and possibly also following his death in 1500. Oates tentatively identified some thirty-five books he felt could be attributed with some certainty to Rotherham.

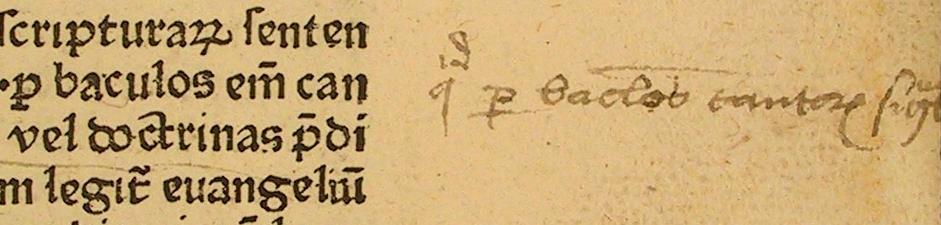

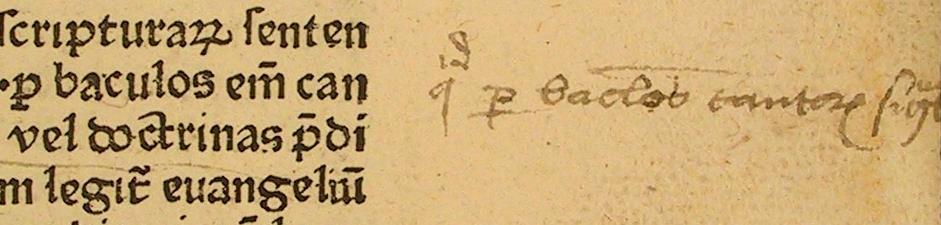

Interestingly, not only is the Durand not included in this list, but it is actually used as an example of a book cited by Pindar, but believed by Oates to be demonstrably not a Rotherham book, based on the fact that it does not appear in the library catalogue of 1556-7.[2] Happily, the cataloguing of the book proves Rotherham’s ownership beyond doubt – an annotation on sig. [b]10r can be matched to Rotherham’s hand from evidence in other incunabula.[3]

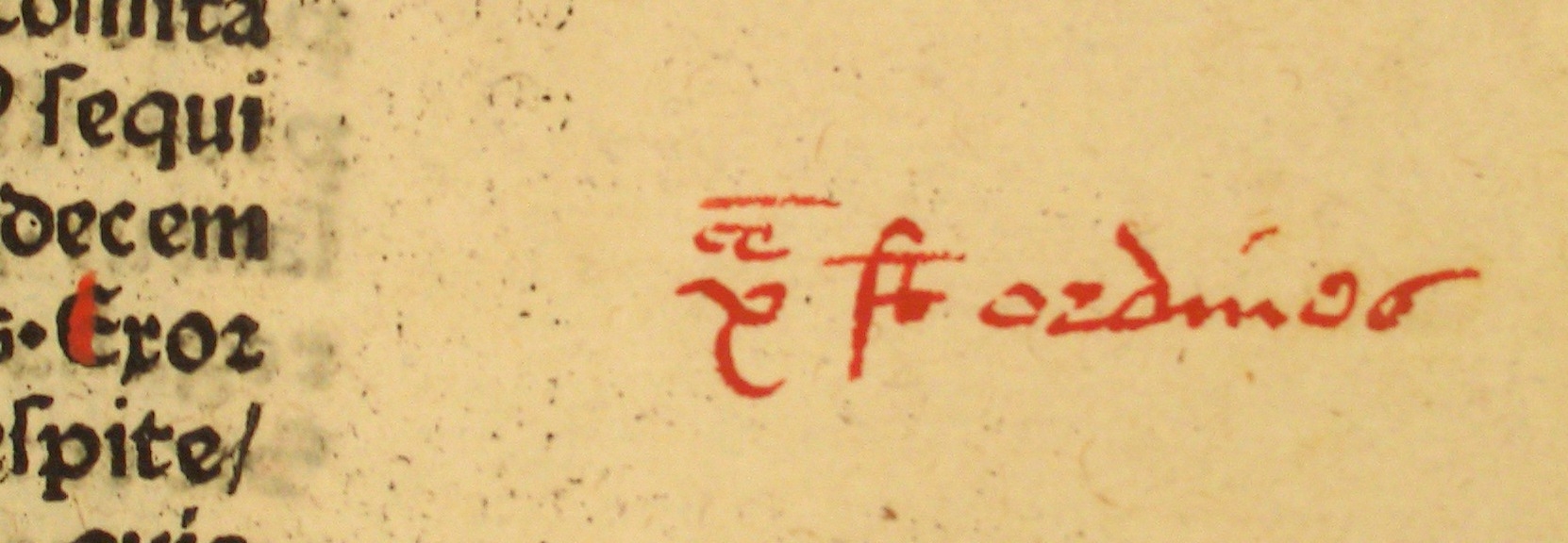

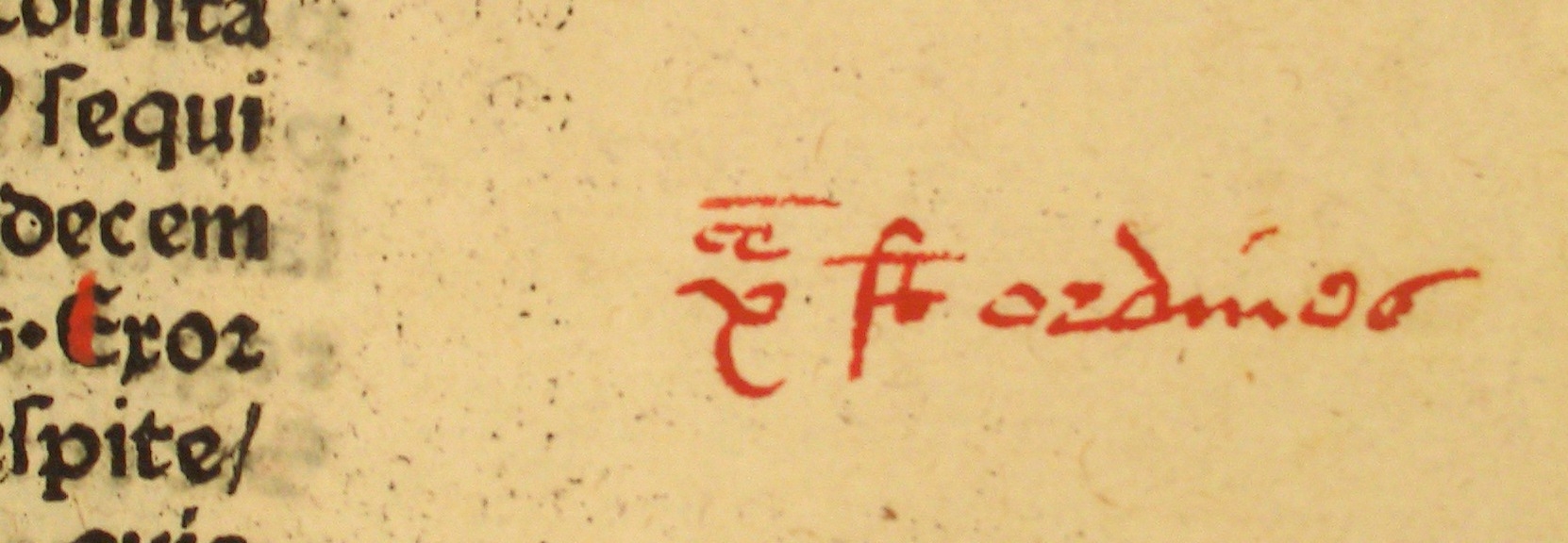

Rebound in plain quarter-blind-ruled calf over pasteboards in the last quarter of the seventeenth century, the Rationale is neither decorated nor rubricated, save one quire. Quire [e] has red paragraph marks and capital strokes supplied, with a note from the rubricator in the right-hand margin.

The presence of a single rubricated quire in the midst of 22 unrubricated is puzzling, but not inexplicable. If multiple copies of the book were stored together prior to binding, some rubricated, others not, quire [e] could conceivably have been substituted with an undecorated instance and mistakenly bound in the CUL copy.

Palaeographical evidence, however, adds a further layer of potential interest. The marginal note features a distinctive rounded letter ‘e’, very characteristic of an English hand, indicative that this particular quire could have been rubricated in England.[4] If this were the case, then in order for quire [e] to become muddled with an undecorated instance multiple copies, some rubricated others not, must have been stored together in England in the fifteenth century. Is this then evidence that the book was imported into England in bulk in sheets in the fifteenth century, then rubricated and sold here? There is ample evidence of this trade taking place,[5] but to extrapolate such from the letterform of a single rounded letter ‘e’ would require a monumental leap of faith!

An alternative hypothesis has quire [e] originating from an entirely different copy of Durand’s Rationale. We most commonly think of imperfections to incunabula being the result of use, neglect or mistreatment, but David McKitterick has convincingly shown that fifteenth-century books could occasionally come from the print shop incomplete. If insufficient sheets were printed or supplied to the binder it was often economically more viable to copy out the missing text by hand rather than set the sheets afresh.[6] McKitterick provides several examples of this practice at CUL, and more have surfaced as part of the incunabula cataloguing project. CUL’s copy of Bartholomaeus’s De proprietatibus rerum ([Basel: Berthold Ruppel, about 1479-80] – ISTC ib00132500), for example, is wanting quire [p], substituted with a contemporary manuscript version on paper bearing a watermark of scales, apparently contemporaneous, and certainly present when the book was first bound.

As well as the insertion of manuscript transcriptions, later book owners could complete an imperfect book by cannibalising other copies. The practice of constructing composite copies is well recognised and was a common practice by the late-eighteenth century. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century collectors sought the crispest, cleanest, tallest, most perfect copies and booksellers, aware that such copies would realise the highest return, were keen to oblige, often advertising that they could complete imperfect books from their standing stock.[7] The CUL Durand, however, is far from a collector’s trophy piece and was in private hands by 1500 – if this is an example of ‘making-good’ an imperfect book it would certainly be one of the earliest recorded. Could the erroneous quire have been added when the book was rebound at the end of the seventeenth century? Again, this seems unlikely. There is no evidence elsewhere that the Library sought to perfect other imperfect books in this way in this period, and quire ‘e’ has the same wide margins as the other quires within the Durand – although a wholly unscientific basis on which to draw a conclusion, the quire certainly ‘feels’ as if it has been part of the book since Rotherham’s ownership.

Are there any useful conclusions to be drawn from the Durand? Not really! The quire could be explained in any number of ways, all equally probable or improbable and none provable. The discussion, however, does make one useful point – in early-printed books it is often the examination of minutiae which opens up the most fruitful paths for research. The smallest, most easily-ignored feature of any book can inform about book use, trade, movement, distribution or production.

[1] Oates, J.T.C.

A Catalogue of the Fifteenth-Century Printed Books in the University Library Cambridge (Cambridge: 1954) vol. 1, p. 2.

[2] Oates, J.T.C. A Catalogue of the Fifteenth-Century Printed Books in the University Library Cambridge (Cambridge: 1954) vol. 1, p.3, footnote 4.

[3] See Inc.1.B.3.17[1419], sig. t10r.

[4] I am grateful to Laura Nuvoloni, Satoko Tokunaga and John Goldfinch for their views on both the rubrication and its explanation.

[5] See Ford, M.L. ‘Importation of printed books into England and Scotland’ in Hellinga, L. and Trapp, J.B. (eds.) The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain volume III 1400-1557 (Cambridge: 1999), pp. 179-201.

[6] McKitterick, D. Print, Manuscript and the Search for Order, 1450-1830 (Cambridge: 2003), pp.107-108.

[7] McKitterick, D. Print, Manuscript and the Search for Order, 1450-1830 (Cambridge: 2003), pp.144-145; Jensen, K. Revol.ution and the Antiquarian Book (Cambridge: 2011), pp. 164-165.

![Inc.1.B.3.1b[1341], [a2]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.B.3.1b1341-a2r-reduced.jpg)

![Inc.1.B.3.1b[1341], My lord chancellor - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.B.3.1b1341-My-lord-chancellor-reduced.png)

![Inc.1.B.3.1b[1341], [x5]r, Moore's annotation - detail - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.B.3.1b1341-x5r-Moores-annotation-detail-reduced.png)

![Inc.1.B.3.1b[1340], [a2]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.B.3.1b1340-a2r-reduced.jpg)

![Inc.5.B.2.5[1147]](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.5.B.2.51147-a1r-reduced-blog2.jpg)

![Inc.7.B.2.26[1270], [a2]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.7.B.2.261270-a2v-reduced.png)

![Inc.7.B.2.26[1270], Virgin and Child - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.7.B.2.261270-Virgin-and-Child-reduced.png)

![Inc.7.B.2.26[1270], [a3]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.7.B.2.261270-a3r-reduced1.png)

![Inc.7.B.2.26[1270], [a3]r - inscription detail - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.7.B.2.261270-a3r-inscription-detail-reduced2.png)

![Inc.5.B.3.2[1363], a1r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.5.B.3.21363-a1r-reduced.jpg)

![Inc.5.B.3.2[1363], Webbe's inscription - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.5.B.3.21363-Webbes-inscription-reduced.png)

![Inc.5.B.3.2[1363], lower cover - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.5.B.3.21363-lower-cover-reduced.jpg)