Richard, Rotherham and the King’s Half-Brother

The discovery of the remains of Richard III in a car park in Leicester prompted me to return to an annotation in a volume discovered and described briefly by my colleague Laura Nuvoloni in 2011. The book is a copy of Bartolus de Saxoferrato, Super secunda parte Digesti novi, printed in Venice by Vindelinus de Spira in 1473, Inc.1.B.3.1b[1341]. An early inscription demonstrates that it was once in the possession of Thomas Rotherham, Archbishop of York and Chancellor of England, and an annotation in it seems to refer to the events of June 1483, when Richard III seized power following the unexpected death of Edward IV.

Its former owner Thomas Rotherham (1423–1500), was a fellow of King’s College during the 1450s, and by 1461 had become one of the new king Edward IV’s chaplains1. He rose steadily (with an intermission during the readeption of Henry VI) during the 1460s and 70s, becoming chancellor of England in 1474 and archbishop of York in 1480. His career suffered a setback in the tumultuous year 1483, when his royal patron unexpectedly died on 9 April. Twenty days later the twelve-year-old heir to the throne, now Edward V, was seized by his uncle Richard of Gloucester at Stony Stratford while journeying to London and his entourage placed under arrest. According to Sir Thomas More, when news of this coup reached the capital, Rotherham temporarily entrusted the Great Seal to Edward IV’s queen Elizabeth Woodville who had taken sanctuary at Westminster. He was deprived of the chancellorship and subsequently arrested at the famous council meeting of 13 June after which William, Lord Hastings was summarily executed. Rotherham was spared and imprisoned in the Tower; Edward V was already there, though presumably at this time in relative comfort in the royal apartments, and would be joined by his little brother Richard of York on the 16th. If contemporary accounts are to be believed, the two young princes were never to emerge; Rotherham was luckier, being released in early July following a heartfelt plea to the new king Richard III from the University of Cambridge, of which he was at that time Chancellor:

Most Cristen and victorious prince we beseche youe to heer our humble prayours. For we must nedes mowrne and sorowe desolate of comfurth vnto we heer and vnderstande your benynge syprite of pyte to hymwarde whiche is a greete prelate in the realme of ynglonde…2

Perhaps it was gratitude for the University’s help in a tight corner that led Rotherham to donate 20 books to Cambridge that year. The University’s Grace Books record that sixpence was paid for listing them3. This was far from the first of Rotherham’s donations to the University and its Library; his name had been entered in the roll of benefactors in 1475 for building a new wing of the Schools, including a library room, and handsomely equipping it with books. Further donations of books followed at intervals, the last apparently in 1493. Three volumes remaining in the collection today bear contemporary donation labels, formerly attached to the upper board under horn, recording their arrival in 1484. Eleven others, including the volume under discussion, have a slightly later inscription “my lord Chawnceler” at the beginning or the end. Fifteen other books can be attributed to Rotherham with varying degrees of probability on other grounds4.

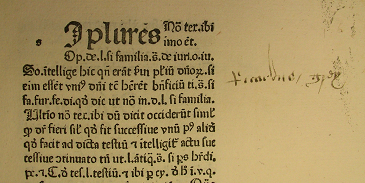

Oates characterised Rotherham’s books as being “for the most part legal commentaries of formidable appearance and bulk” and this is certainly true of Bartolus’s Super secunda parte Digesti novi, a mighty folio of 346 leaves containing a detailed commentary on Justinian’s Digest. Once an essential reference tool, this book must have long lain unread, and it would hardly merit a glance today were it not for some early annotations apparently in Rotherham’s hand. Most interesting of these is the name “Ricardus grey” written next to the paragraph “Si plures” (book 47, chapter 10, section 34). The meaning and even the text of the passage it stands by is hard to decipher, printed as it is in heavily abbreviated legal Latin, but the text of the Digesta to which it refers reads at this point:

Si plures servi simul aliquem ceciderint aut convicium alicui fecerint, singulorum proprium est maleficium et tanto maior iniuria, quanto a pluribus admissa est. Immo etiam tot iniuriae sunt, quot et personae iniuriam facientium.

This may be roughly rendered as:

If several servants kill or attack someone at the same time, the blame lies on each of them, and the more people commit the crime, the greater it becomes. In other words, there are as many crimes committed as there are people who commit them.

The name “Ricardus Grey” which appears next to this may refer to Sir Richard Grey, younger son of Queen Elizabeth Woodville by her first marriage and hence half-brother to Edward V. He was an important member of the young Edward’s household and council at Ludlow and was one of those arrested at Stony Stratford on April 29 1483 on charges of conspiring against the Duke of Gloucester; among the others were the prince’s tutor Anthony Woodville, Earl Rivers, military hero, brother to Queen Elizabeth and patron to William Caxton, and Edward’s chamberlain Sir Thomas Vaughan5. All were sent north under guard, and Grey was confined at Richard’s castle in Middleham. The royal duke’s moves to have all three executed were resisted by the royal council, but on 10 June Gloucester summoned troops from the North to put down another alleged conspiracy. Grey and Woodville were taken to Pontefract where, on 25 June, they were executed along with Vaughan in front of the assembled soldiers. The following day, 530 years ago today, Richard took his seat on the King’s bench and began his reign as Richard III.

Few personal documents from this time survive and even fewer refer to political events. Those that do tend to be cryptic, and this marginal annotation is no exception. It is hard however to resist the notion that the addition of a name now obscure but probably well-known to Rotherham’s contemporaries opposite a passage referring to unlawful killing is a comment on the events of that turbulent year.

1 H.L. Bennett, Archbishop Rotherham (Lincoln, 1901), p. 36; J.C.T. Oates, Cambridge University Library: a History (Cambridge, 1986), p. 38.

2 University Grace Book A, p. 171-2, quoted in Oates, op. cit., p. 39.

3 Grace Book A, f. 136b, quoted in H.R. Luard, A Chronological List of the Graces, Documents, and Other Papers in the University Registry which Concern the University Library (Cambridge, 1870), p. 2.

4 J.C.T. Oates, A catalogue of the Fifteenth-Century Printed Books in the University Library, Cambridge (Cambridge, 1954), p. 3

5 Michael Hicks, Edward V, the Prince in the Tower (Stroud, 2003), p. 142-3 and passim