An Elephant in the Bindings: A Rare Appearance ?

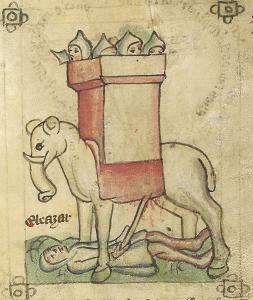

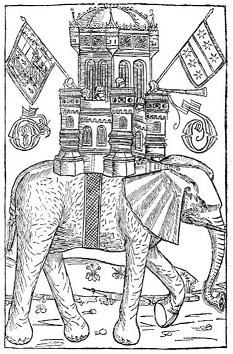

This small but intriguing tool is found on the beautiful early Renaissance bindings of four of our incunabula. It shows a four-legged animal with a long protruding nose carrying a square basket on its back, which is covered with a tasselled rug, and flying a flag bearing a cross. The image immediately brings to the mind representations of war elephants carrying warriors in their howdah, and it seems to me that this little tool also represents an elephant.

The incunabula belong to a group of five books containing texts from the Corpus iuris civilis, the collection of Roman laws issued by Holy Roman Emperors from Justinian I (483?-565) onwards. The books had been printed in Venice by Baptista de Tortis between November 1497 and February 1499 (ISTC ij00553000, ij00562000, ij00572000, ij00587400, and ij00599000; CUL Inc.0.B.3.53[1543], Inc.0.B.3.53[1544], Inc.0.B.3.53[1546], Inc.0.B.3.53[1547], Inc.0.B.3.53[1548]), but travelled North soon afterwards as their first pages are all decorated with pen-flourished initials in a Northern style, possibly Dutch.

![Inc.0.B.3.53[1546], upper free endpaper - watermark](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Watermark-in-Inc.0.B.3-reduced.jpg) The watermarks of the upper free endpapers found in four of the books represent a coat-of-arms (quartered, 1 and 4 a fleur-de-lys, 2 and 3 a dolphin; over it a crown with four strawberry leaves) and are similar to two twin watermarks found in books printed by Richardus Pafraet in Deventer in 1500 (see Watermarks in Incunabula printed in the Low Countries (WILC), WM I 55725 and WM I 55726). All these elements seem to suggest a Dutch provenance for the bindings as well. This hypothesis is further supported by the close resemblance of our bindings to two others in the Huntington Library which have been temptatively attributed to Antwerp (Huntington Library 102122 and 99095).

The watermarks of the upper free endpapers found in four of the books represent a coat-of-arms (quartered, 1 and 4 a fleur-de-lys, 2 and 3 a dolphin; over it a crown with four strawberry leaves) and are similar to two twin watermarks found in books printed by Richardus Pafraet in Deventer in 1500 (see Watermarks in Incunabula printed in the Low Countries (WILC), WM I 55725 and WM I 55726). All these elements seem to suggest a Dutch provenance for the bindings as well. This hypothesis is further supported by the close resemblance of our bindings to two others in the Huntington Library which have been temptatively attributed to Antwerp (Huntington Library 102122 and 99095).

Indeed, confirmation that the books were in the Low Countries in the late 16th or early 17th century comes from the name “Arnoldus de Gruithuis” inscribed twice on the upper free endpaper of the copy of Justinianus, Digestum novum, dated 12 February 1498/99 (Inc.0.B.3.53[1546]).

Arnold is possibly identifiable with the Arnold de Gruithuis who inherited a fief from Doorwerth Castle, near Arnhem, on 30 October 1626 following the death of his uncle Adam van der Hoeven [see J.C. Kort. Repertorium op de lenen van de Hofstede Doorwerth (1330) 1377-1743 (1758), available at http://www.hogenda.nl/wp-content/plugins/hogenda-search/download_attachment.php?id=9705&type=loanroom]. The surname Gruithuis also suggests that he may have been a member of the rich and powerful Gruuthuse family of Bruges, and therefore a possible distant relative of the courtier and patron of the arts Louis de Gruuthuse (c. 1422-1492), whose library included the famous “Gruuthuse manuscript“, a unique 14th- and early 15th-century collection of vernacular poetry in Dutch, and a number of illuminated manuscripts commissioned by him from the best Flemish artists of his time.

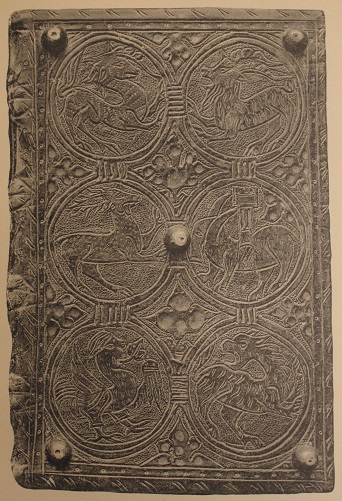

The origin of the image of a war elephant for the binding tool is unknown. It is apparently a very rare iconography in the world of medieval bookbinding. A very quick and superficial survey of the reference publications on medieval and renaissance bindings available in our Reading Room supplied me with only one other example. A war elephant is one of the six animals (the others being a Capricorn, a deer, a stag, a bird and a dog respectively) represented in six medallions carved in the leather of the upper cover of the Gothic binding of the “Weistum der stadt Erfurt”, a manuscript containing the laws of the German town of Erfurt up to 1387 (now Erfurt Stadtarchiv, 2/100-4; the binding is reproduced in Martin Bollert, Lederschnittbände des XIV. jahrhunderts, Leipzig, 1925, pl. 29, and F. A. Schmidt-Kunsemuller, Corpus der Gotischen Lederschnitteinbande aus dem Deutschen Sprachgebiet, Stuttgart, 1980, p. 13, no. 74).

Like the tool in our bindings, the Gothic elephant is seemingly represented carrying a howdah on its back, which is again protected by a rug.

The image harks back to medieval representations of elephants in Western Europe. Similar images of war elephants recurs in medieval frescoes, such as the image of the elephant with a castle on its back inspired by Muslim motifs and painted after 1125 (possibly between 1129 and 1234 as its companion frescoe of the camel transferred onto to canvas and now in the Metropolitan Museum of New York) by the Catalan Master of Tahull in the Mozarabic Hermitage of San Baudelio de Berlanga in Spain.

The image harks back to medieval representations of elephants in Western Europe. Similar images of war elephants recurs in medieval frescoes, such as the image of the elephant with a castle on its back inspired by Muslim motifs and painted after 1125 (possibly between 1129 and 1234 as its companion frescoe of the camel transferred onto to canvas and now in the Metropolitan Museum of New York) by the Catalan Master of Tahull in the Mozarabic Hermitage of San Baudelio de Berlanga in Spain.

War elephants had been known in the West at least since the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC when Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon, 20/21 July 356 – 10/11 June 323 BC) defeated the King of Persia Darius III, (c. 380 – July 330 BC), whose powerful army included no less than fifteen elephants. The general Hannibal Barca of Carthage (247-183/182 BC) made use of war elephants in his campaigns against Rome between the spring of 218 BC and October 202 BC. The image of an elephant lead by its mahout (i.e. its keeper) can be found in a silver double shekel coin of Carthage dating to around 230 BC [London, British Museum, CM 1911-7-2-1 (IGCH 2328)]. Despite the fact that Hannibal’s mighty army, strong of 80 war elephants, was eventually defeated at Zama by the Roman army lead by Publius Cornelius Scipio (236-183 BC), generally known as Scipio Africanus thereafter, the awe-inspiring beasts certainly casted a lasting impression in people’s imagination.

War elephants had been known in the West at least since the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC when Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon, 20/21 July 356 – 10/11 June 323 BC) defeated the King of Persia Darius III, (c. 380 – July 330 BC), whose powerful army included no less than fifteen elephants. The general Hannibal Barca of Carthage (247-183/182 BC) made use of war elephants in his campaigns against Rome between the spring of 218 BC and October 202 BC. The image of an elephant lead by its mahout (i.e. its keeper) can be found in a silver double shekel coin of Carthage dating to around 230 BC [London, British Museum, CM 1911-7-2-1 (IGCH 2328)]. Despite the fact that Hannibal’s mighty army, strong of 80 war elephants, was eventually defeated at Zama by the Roman army lead by Publius Cornelius Scipio (236-183 BC), generally known as Scipio Africanus thereafter, the awe-inspiring beasts certainly casted a lasting impression in people’s imagination.

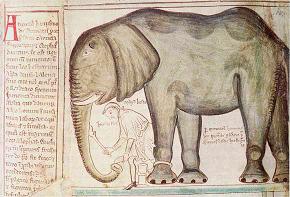

In the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, elephants were sometimes used as diplomatic gifts to kings, emperors and popes. We don’t have images of Abul-Abbas or Abulabaz, the Asian elephant sent in 798 to the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne by the Caliph of Baghdad Harun al-Rashid, but the elephant depicted with its keeper in one of the manuscripts of the Chronica Maiora II by the Benedictine monk and chronicler Matthew Paris (c. 12oo – 1259), Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Parker Library, MS 16I, fol. ii recto, is said to be a drawing from life of the elephant given by the king of France Louis IX to Henry III of England in 1255.

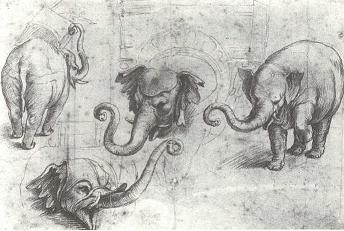

In the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, elephants were sometimes used as diplomatic gifts to kings, emperors and popes. We don’t have images of Abul-Abbas or Abulabaz, the Asian elephant sent in 798 to the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne by the Caliph of Baghdad Harun al-Rashid, but the elephant depicted with its keeper in one of the manuscripts of the Chronica Maiora II by the Benedictine monk and chronicler Matthew Paris (c. 12oo – 1259), Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Parker Library, MS 16I, fol. ii recto, is said to be a drawing from life of the elephant given by the king of France Louis IX to Henry III of England in 1255.  Images from life of Hanno (c. 1510-8 June 1516) [Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, Four Studies of an Elephant, Parker II (1956) 590)] and Suleiman (ca. 1540-18 December 1553), the two young elephants donated by King Manuel I of Portugal and his son John III to Pope Leo X and Prince Maximilian of Habsburg (the future Emperor Maximilian II of Austria) respectively, were captured during their short lives in Rome and Vienna by Raphael, Giulio Romano and other contemporary artists.

Images from life of Hanno (c. 1510-8 June 1516) [Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, Four Studies of an Elephant, Parker II (1956) 590)] and Suleiman (ca. 1540-18 December 1553), the two young elephants donated by King Manuel I of Portugal and his son John III to Pope Leo X and Prince Maximilian of Habsburg (the future Emperor Maximilian II of Austria) respectively, were captured during their short lives in Rome and Vienna by Raphael, Giulio Romano and other contemporary artists.

These sophisticated images, though, are rather distant from the elephant in our small binding tool, which instead resembles to the more fanciful representations of war elephants as they appear in another portion of Matthew Paris manuscript, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Parker Library, MS 16II, fol. 152v, as well as in a 12th-century copy of Orosius, Historia adversus paganus, from the Augustinian priory of the Holy Trinity or Christ Church at Kirkham, Yorkshire (London, British Library, Burney MS. 216, fol. 33 recto).

These sophisticated images, though, are rather distant from the elephant in our small binding tool, which instead resembles to the more fanciful representations of war elephants as they appear in another portion of Matthew Paris manuscript, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Parker Library, MS 16II, fol. 152v, as well as in a 12th-century copy of Orosius, Historia adversus paganus, from the Augustinian priory of the Holy Trinity or Christ Church at Kirkham, Yorkshire (London, British Library, Burney MS. 216, fol. 33 recto).  In fact, I found images of elephants, including thirteen war elephants, in 23 other medieval manuscripts in the British Library, ranging from the second quarter of the 13th century to the 1480s (British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts), including a copy of the Speculum humanae salvationis from the Low Countries and datable to the second half of the 14th century (British Library, Sloane MS. 361, fol. 27 recto).

In fact, I found images of elephants, including thirteen war elephants, in 23 other medieval manuscripts in the British Library, ranging from the second quarter of the 13th century to the 1480s (British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts), including a copy of the Speculum humanae salvationis from the Low Countries and datable to the second half of the 14th century (British Library, Sloane MS. 361, fol. 27 recto).

This more standardised imagery of a war elephant, which has come to be known as the “elephant and castle”, can also be found in other medieval artefacts and I recently saw a late-medieval one carved at one end of a pew in St Andrew’s Church, South Lopham, Norfolk. As my colleague Iain B. commented, “the elephant has a beak instead of a trunk, and hooves as well” [image courtesy of Iain].

This more standardised imagery of a war elephant, which has come to be known as the “elephant and castle”, can also be found in other medieval artefacts and I recently saw a late-medieval one carved at one end of a pew in St Andrew’s Church, South Lopham, Norfolk. As my colleague Iain B. commented, “the elephant has a beak instead of a trunk, and hooves as well” [image courtesy of Iain].

The same imagery was also the probable source of inspiration for a device found in two slightly different versions in two Dutch editions datable to the late 1480s.  The first version has “the elephant facing the right, surmounted by a castle with warriors, with two banners displaying the arms of Gouda and of the Archduke Maximilian; the initials G.D. to left and right” [Catalogue of books printed in the XVth century now in the British Museum [British Library], vol. IX, London, 1962, p. 38], and can be found in the Historie hertoghe godevaerte van boloen, i.e. the Dutch translation of Godefrey of Boloyne, or The siege and conquest of Jerusalem, attributed to a printer working in Gouda around 1486-87 (ISTC ig00317000). The second is very similar to the previous one, but “freshly cut”, smaller in size and with the elephant turned to the left. It is found in the second incunable edition of Le chevalier délibéré by Olivier de la Marche, also possibly printed in Gouda by the same anonymous printer after 31 October 1489 (ISTC il00029010). Both editions are lavishly illustrated by cycles of newly cut woodcuts and therefore stand out from the rather modest outputs produced by contemporary Gouda printing presses. For this reason, even though both editions have been temptatively assigned to the press of the Collaciebroeders, the devices have been attributed to a patron rather than a printer (see Catalogue … [British Library], cit. above, p. 38, and Wytze Hellinga and Lotte Hellinga, The Fifteenth-Century Printing Types of The Low Countries, vol. 1, Amsterdam, 1966, pp. 85-6 and 88).

The first version has “the elephant facing the right, surmounted by a castle with warriors, with two banners displaying the arms of Gouda and of the Archduke Maximilian; the initials G.D. to left and right” [Catalogue of books printed in the XVth century now in the British Museum [British Library], vol. IX, London, 1962, p. 38], and can be found in the Historie hertoghe godevaerte van boloen, i.e. the Dutch translation of Godefrey of Boloyne, or The siege and conquest of Jerusalem, attributed to a printer working in Gouda around 1486-87 (ISTC ig00317000). The second is very similar to the previous one, but “freshly cut”, smaller in size and with the elephant turned to the left. It is found in the second incunable edition of Le chevalier délibéré by Olivier de la Marche, also possibly printed in Gouda by the same anonymous printer after 31 October 1489 (ISTC il00029010). Both editions are lavishly illustrated by cycles of newly cut woodcuts and therefore stand out from the rather modest outputs produced by contemporary Gouda printing presses. For this reason, even though both editions have been temptatively assigned to the press of the Collaciebroeders, the devices have been attributed to a patron rather than a printer (see Catalogue … [British Library], cit. above, p. 38, and Wytze Hellinga and Lotte Hellinga, The Fifteenth-Century Printing Types of The Low Countries, vol. 1, Amsterdam, 1966, pp. 85-6 and 88).

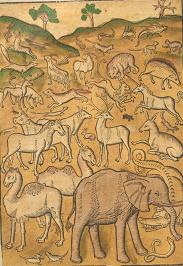

Given the abundance of elephant images in medieval artefacts, I should not have been so surprise to find the tool of a war elephant in our bindings.  As it was the case with the arrival of the young elephants in Rome and Vienna, the transit of an elephant through several towns in Holland in 1484 may well have inspired the realistic representation of an elephant on leaf Q2 verso of the Dutch translation of De proprietatibus rerum by Bartholomaeus Anglicus, printed in Haarlem by Jacob Bellaert with the title Van den proprieteyten der dinghen on 24 December 1485 (ISTC ib00142000), but also sparked the representation of a war elephant in the devices of Gouda editions from “the howdah on the elephant’s back and the identity of the word in sound with the name of the town [of Gouda]”, as suggested by Henry Bradshaw (A Classified Index of the Fifteenth Century Books in the De Meyer Collection sold at Ghent, November, 1869 (Memorandum no. 2), London, 1870, Note C, p. 14; repr. Collected Papers by Henry Bradshaw, XI, 206-236, pp. 219-220).

As it was the case with the arrival of the young elephants in Rome and Vienna, the transit of an elephant through several towns in Holland in 1484 may well have inspired the realistic representation of an elephant on leaf Q2 verso of the Dutch translation of De proprietatibus rerum by Bartholomaeus Anglicus, printed in Haarlem by Jacob Bellaert with the title Van den proprieteyten der dinghen on 24 December 1485 (ISTC ib00142000), but also sparked the representation of a war elephant in the devices of Gouda editions from “the howdah on the elephant’s back and the identity of the word in sound with the name of the town [of Gouda]”, as suggested by Henry Bradshaw (A Classified Index of the Fifteenth Century Books in the De Meyer Collection sold at Ghent, November, 1869 (Memorandum no. 2), London, 1870, Note C, p. 14; repr. Collected Papers by Henry Bradshaw, XI, 206-236, pp. 219-220).

![Inc.0.B.3.53[1546] - Elephant tool](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Elephant-tool-small.jpg) The attribution of the devices to a patron rather than a printing press seems to confirm my own hypothesis that the small binding tool representing an “elephant and castle” in our bindings may provide a clue for the identification of their late 15th– or early 16th-century owner rather than the binder and, consequently, an explanation for its rarity among medieval and Renaissance bindings.

The attribution of the devices to a patron rather than a printing press seems to confirm my own hypothesis that the small binding tool representing an “elephant and castle” in our bindings may provide a clue for the identification of their late 15th– or early 16th-century owner rather than the binder and, consequently, an explanation for its rarity among medieval and Renaissance bindings.

P.S. The odyssey of Suleiman from Lisbon to Vienna was vividly recounted in a mixture of fact, fable and fantasy by Jose Saramago, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998, in his novel The Elephant’s Journey published in Lisbon in 2008.

![Inc.0.B.3.53[1546], upper board - Elephant tool](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Elephant-tool4.png)

![Inc.0.B.3.53[1546], fol. a2r - initial](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Inc.0.B.3.531546-fol.-a2r-initial-reduced.png)

![Inc.0.B.3.53[1547], fol. a2r - initial](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Inc.0.B.3.531547-fol.-a2r-initial-reduced-2.png)

![Inc.0.B.3.53[1546], upper board](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Inc.0.B.3.531546-upper-board-reduced.png)

![Inc.0.B.3.53[1546], upper free endpaper, inscription](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Arnoldus-de-Gruithuis.jpg)