Felice Feliciano annotator of Valturio, De re militari, 1472

The second copy was donated to the library by Samuel Sandars in 1894 (SSS.4.14). In rather worse physical condition than the other copy, this second exemplar is in fact more important in the history of the edition itself as the manuscript captions to the woodcut images of war machines are in the hand of Felice Feliciano (1433-ca. 1480), the “antiquarius”, humanist, scribe, artist, binder, alchemist, goldsmith, and typographer from Verona, who was one of the most eccentric and inventive protagonists of the Italian Renaissance.

The captions were added by Feliciano partly in epigraphic capitals and partly in humanistic cursive minuscule.

He also wrote the heading on the first page of the treatise in his characteristic epigraphic capitals of alternating blue and red [my attribution to Feliciano’s hand of the manuscript additions was kindly confirmed by Stefano Zamponi in private correspondence].

Feliciano’s hitherto unnoticed contribution to the Cambridge University Library Valturio is less extensive but nevertheless comparable to his rubrications in the Vatican Library copy (Stampato Rossiano 1335), which was first discovered by Augusto Campana, who wrote about it in a famous article published in 1940 (“Felice Feliciano e la prima edizione del Valturio”, Maso Finiguerra, V.3 (1940), 211-222).

In the Vatican copy Feliciano also applied the same system of catchwords or symbols to signal the end of quires, and supplied coloured initials, titles and rubrics to the books and chapters, as well as running titles, whereas he left the rubrication of the Cambridge copy incomplete.

In the Vatican copy Feliciano also applied the same system of catchwords or symbols to signal the end of quires, and supplied coloured initials, titles and rubrics to the books and chapters, as well as running titles, whereas he left the rubrication of the Cambridge copy incomplete.

The captions to the woodcut images did not originate with Feliciano: they reproduce the captions devised by Valturio himself to accompany the drawings of the war machines in the seven manuscripts written under his direct supervision by the scribe Sigismundus Nicolai Alemannus, including Vat. Urb. lat. 281, the earliest manuscript signed by Sigismondus in 1462, and Firenze, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Pluteo xlvi.3, copied around 1472, i.e. the same year as the Verona edition: http://teca.bmlonline.it/TecaViewer/index.jsp?RisIdr=TECA0000534757

The captions were therefore an essential part of Valturio’s original text. Consequentially, they were also faithfully reproduced in the fourteen other extant manuscripts of his work signed by or attributed to other scribes, including a manuscript in the Riccardiana Library in Florence, Riccardiano 794 (cf. http://www.istitutodatini.it/biblio/images/it/riccard/794/), which has been identified by Teresa de’ Robertis as being in the hand of Feliciano himself and possibly produced in the late 1460s or the 1470s (Teresa De Robertis, “Feliciano copista di Valturio”, in Tra libri e carte. Studi in onore di Luciana Mosiici, ed. by T. De Robertis and G. Savino, Firenze, 1998, 73-97).

In the manuscripts the captions were added in colour, usually light purple ink, next to the technical drawings of the war machines at the same time as the decoration, i.e. after the copying of the text. It is not surprising, therefore, that they came to be considered as part of the rubrication and, as a result, remained unprinted in the 1472 edition in order to be added by hand at a later stage. In consequence, they are absent from surviving copies of the edition which were never rubricated. In other copies, however, it was the rubricators supplying the titles to the individual books and the running titles who omitted them, as in the Sulzbach copy in the Cambridge University Library and in the exemplars held in the Bodleian Library in Oxford (Bod-Inc V-041).

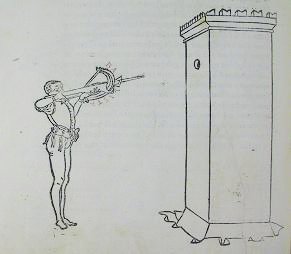

These omissions were regarded as mistakes by Paolo Ramusio, the editor of the second edition of Valturius’s work, printed in Verona by Bonino Bonini in 1483 (Inc.2.B.19.4[2163]). In his introduction Ramusio stated that his aim was to restore Valturio’s text to its original form and integrity. In Ramusio’s edition, therefore, the captions to the illustrations were duly printed as part of the text, as can be seen when we compare the images that illustrate how to measure the height of a tower in copies of the first and secon editions.

Ramusio’s complaints seem amply justified given Feliciano’s occasional carelessness in reproducing the woodcut captions: see the repetition and cancellation of a word on fols [r8] verso and [s6] verso of the incunable SSS.4.14 , and the omission of the letter “T” in the word “INSTRVMENTVM” on fol. 131v of the Riccardiano manuscript 194 .

The discovery of Feliciano’s hand in the Cambridge exemplar of the 1472 edition adds this book to the number of his known manuscripts. However, we are still left with the open question whether he actively collaborated in the making of the printed edition and its illustrations. Our knowledge of Feliciano’s life is still sketchy, but it seems that around 1471-1472, at the time the book was produced, he was not residing in Verona but in Bologna and Ferrara. It is of course possible that Feliciano was simply requested to annotate some copies of the edition during a short visit to his home town. We do know, however, that in 1475 and again in 1476 he was directly involved in the production of printed books: in the autumn of 1475 he collaborated with the typographer Severino da Ferrara in the publication of Baldassare da Fossombrone’s poem Il menzognero ovvero Bosadrello, Albertus Trottus’s De vero et perfecto clerico, and Angelus de Gambilionibus’s Tractatus de maleficiis, and Benevenutus Grassus’ s De oculis eorumque aegritudinibus et curis (ISTC ib00034200, ISTC it00478000, ISTC ig00060500, ISTC ig00352000). He was also apparently involved in the printing of an antisemitical text in Verona on 22 May 1475. Finally, on 1 October 1476, he and Innocente Ziletti put their joint names on the edition of Petrarch’s De viris illustribus in the Italian translation by Donato degli Albanzani (ISTC ip00415000).

Feliciano’s printing ventures are perhaps unsurprising when we consider that in 1460 he had been identified as aurifex, i.e. goldsmith, in his brother Andrea’s will: it is a well known fact that goldsmiths, such as Gutenberg, Ratdolt and Jenson, played a pivotal role in the development of the printing industry in 15th-century Europe. Nevertheless, no documentary evidence of his involvement in the production of the 1472 Valturius edition has surfaced so far. The two rubricated copies in the Vatican and Cambridge University Library, are too small a sample to confirm this hypothesis and the question must remain for the moment unanswered. Only a long overdue complete survey of all the 76 extant copies of the edition, possibly combined with a critical edition of the printed text in comparison with the manuscript tradition, and an analysis of Feliciano’s copy in particular, may provide us with an answer.

For the time being, I can only say with confidence that Feliciano’s hand is not present in the two Oxford exemplars, Douce 267 and 289, whose rubrication has been described as “in the style of Felice Feliciano” in the catalogue of the Bodleian incunables (Bod-Ink V-041; reproductions of the two books were kindly provided to me by Irene Ceccherini, courtesy of the Bodleian Library). The illuminated initials in Douce 289 are very close in style to those found in the copies of the edition held in the Biblioteca Civica in Verona (Inc. 1084) and the Biblioteca Universitaria in Padova (Sec. XV. 677), where we also find the same rubricator, giving the impression that these copies were rubricated and illuminated “in series”.

Bibliography

Augusto Campana, “Felice Feliciano e la prima edizione del Valturio”, Maso Finiguerra, V.3 (1940), 211-222.

Daniela Fattori, “Spigolature su Felice Feliciano da Verona”, La Bibliofilia, XCIV.3 (1992), 263-269.

L’ ‘Antiquario’ Felice Feliciano 1995: L’ ‘Antiquario’ Felice Feliciano veronese. Tra epigrafia antica, letteratura e arti del libro. Atti del Convegno di Studi, Verona 1993, ed. A. Contò and L. Quaquarelli, Padua, 1995 (Medioevo e Umanesimo, 89), in particular Agostino Contò, “Non scripto calamo. Felice Feliciano e la tipografia”, 289-312.

Agostino Contò in Mantegna e le Arti a Verona 2006: Mantegna e le Arti a Verona 1450-1500, [exhibition catalogue], ed. S. Marinelli and P. Marini, Venice, 2006, 455-6, no. 188.

Donatella Frioli, “Per la tradizione manoscritta di Roberto Valturio. Appunti e spunti di ricerca”, in Roberto Valturio, De re military. Saggi critici, ed. by Paola Delbianco, Rimini and Milan, 2006, 69-93.

Agostino Conto’, “Da Rimini a Verona: le edizioni quattrocentesche del De re militari”, in Roberto Valturio, cit., 95-104.

Donatella Frioli, “Da Rimini a Verona: Roberto Valturio, Domenico Foschi e Felice Feliciano”, in Virtute et labore. Studi offerti a Giuseppe Avarucci per i suoi settant’anni, ed. by Rosa Maria Borraccini and Giammario Borri, II, Spoleto, 2008, 1073-1109.

![SSS.4.14, [r10]r - reduced - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/SSS.4.14-r10r-reduced-blog11.jpg)

![SSS.4.14, [r9]v - reduced - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/SSS.4.14-r9v-reduced-blog2.jpg)

![SSS.4.14, [r9]v - detail - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/SSS.4.14-r9v-detail-blog.jpg)

![SSS.4.14, [r10]r - detail - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/SSS.4.14-r10r-detail-blog.jpg)

![SSS.4.14, fol. [a1]r - reduced - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/SSS.4.14-fol.-a1r-reduced-blog4.jpg)

![SSS.4.14, [c5]v - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/SSS.4.14-c5v-blog3.jpg)

![Inc.2.B.19.4[2163], c7v - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Inc.2.B.19.42163-c7v-blog11.jpg)

![SSS.4.14, fol. [r8]v - blog detail of caption](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/SSS.4.14-fol.-r8v-blog-detail-of-caption.jpg)

![SSS.4.14, fol. [s6]v - blog detail](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/SSS.4.14-fol.-s6v-blog-detail1.jpg)