This is a cry for help ! Recent additions and amendments to the online library catalogue Newton by the incunable project include the descriptions of seven small books printed between circa 1495 and 1515 and bound together in a small Sammelband that came to the library from an unknow source before 1700, now Dd*.5.60(G). The seven booklets are preceded in the volume by three later editions, whose list is as follows: Petrus Cudsemius, De desperata Calvini causa tractatus brevis. Mainz: Johannes Albinus, 1609 [lacking title page] – Martin Luther, De usura taxanda ad pastores ecclesiarum commonefactio, in the Latin translation by Johannes Freder. Frankfurt am Main : [Petrus Brubachium], 1554 – Gabriel Valliculus, De liberali Dei gratia & seruo hominis arbitrio. Nurimberg: Johannes Guldenmundt, 1536. Almost all the books in the volume had already been catalogued in Newton: the three later editions had been correctly identified, but the descriptions of late 15th- or early 16th-century editions, many of which with woodcut illustrations, were either incomplete, incorrect, or missing altogether, as it was the case of an edition of Brigitta’s Orationes and a copy of the Divisione decem nationum. As I set to put things in order I realised that their identification was in fact proving rather challenging. Hence my appeal for help !

Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 6:

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a1]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a1v-reduced.png)

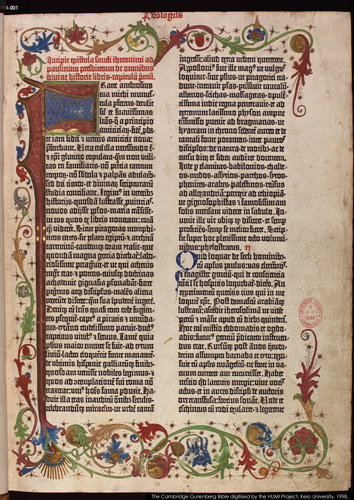

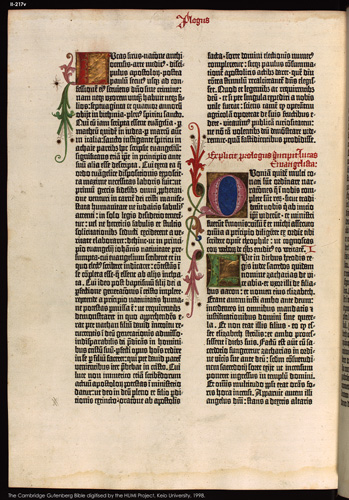

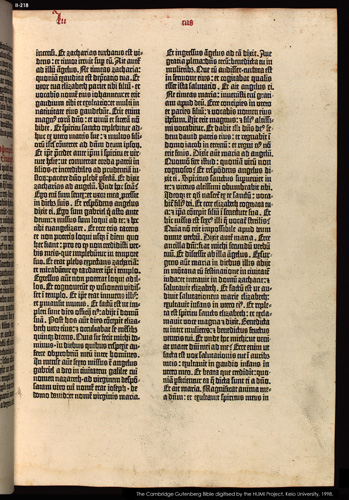

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a1r-reduced.jpg) The sixth booklet in the volume, Orationes sanctae Brigittae cum oratione sancti Augustini, was the only one described by Oates in his catalogue of the 15th-century books in the University Library (Oates 1571; for all publications mentioned in the post, see bibliography below). Oates identified it with an edition that is generally assigned to Eucharius Silber in Rome around 1495 (but 1498 by Vera Sack in the Freiburg catalogue, no. 695): see ISTC ib00679200. Images of a copy held in the National Library of Sweden in Stockholm, provided by the online version of GW 4370, confirmed the identification, and therefore I had no problem in creating a new record for this edition in Newton, Dd.5.60.G, item no. 6. [Images: leaves [a1] recto, [a1] verso, [a5] verso, [a6] recto and [a7] verso. For better resolution, please click on each image].

The sixth booklet in the volume, Orationes sanctae Brigittae cum oratione sancti Augustini, was the only one described by Oates in his catalogue of the 15th-century books in the University Library (Oates 1571; for all publications mentioned in the post, see bibliography below). Oates identified it with an edition that is generally assigned to Eucharius Silber in Rome around 1495 (but 1498 by Vera Sack in the Freiburg catalogue, no. 695): see ISTC ib00679200. Images of a copy held in the National Library of Sweden in Stockholm, provided by the online version of GW 4370, confirmed the identification, and therefore I had no problem in creating a new record for this edition in Newton, Dd.5.60.G, item no. 6. [Images: leaves [a1] recto, [a1] verso, [a5] verso, [a6] recto and [a7] verso. For better resolution, please click on each image].

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a5]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a5v-reduced.png)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a7]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a7v-reduced.png)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a6]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a6r-reduced1.png)

The other early editions proved more difficult, though, as I found unconvincing some of the attributions that Oates provided for them within his description of Brigitta’s Orationes.

Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 4:

The first early edition to be found in the volume, i.e. its fourth item, is a copy of Andreas de Escobar, Modus confitendi. The book had been previously identified by Oates with one of the editions printed in Rome by Johann Besicken after 1500 [Images: leaves [a1] recto, [a1] verso and [b4] recto].

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 4, [a1]r, detail - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-4-a1r-detail-reduced4.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 4, [b4]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-4-b4r-reduced7.jpg)

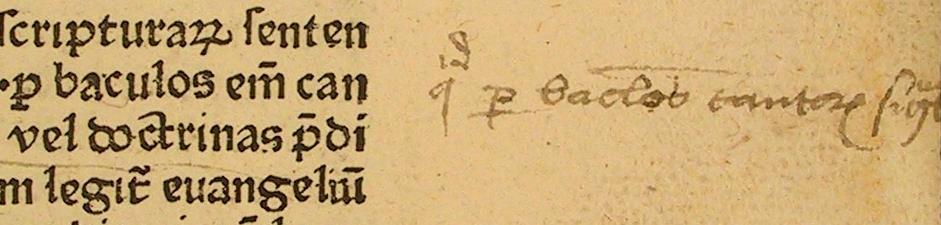

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 4, [a1]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-4-a1v-reduced4.jpg) Indeed, our booklet shows the same number of leaves and lines, i.e. 12 leaves with 23 lines to the page, as the editions of this text assigned to Besicken in ISTC. It also shows the same impronta or fingerprint (ieui oset abe* pcco) given for an edition attributed to Besicken around 1504 in the online version of the Censimento nazionale delle edizioni italiane del XVI secolo (EDIT16), the Italian national census of 16th-century printed books [EDIT 16 (2. ed.): CNCE 18284]. This and the other Besicken editions, however, seem to differ from our booklet in the leaf signatures [with the only exception of the edition described in GW 1803 (ISTC ia00682000)], the typesettings of the initial captions, incipits, and explicits. Moreover, the Gothic type used in our edition, measuring 86 mm. per 20 lines, and with characteristic capital letters A, F, M and Q, among other features, can be identified with Eusebius Salber’s 92 G [P. 6] rather than Johann Besicken’s 87 G.a [P. 1], which is close but not identical (see BM 15th cent., IV, 103 and 138, and pls X* and XII*). This type was also used in an edition of the Translatio

Indeed, our booklet shows the same number of leaves and lines, i.e. 12 leaves with 23 lines to the page, as the editions of this text assigned to Besicken in ISTC. It also shows the same impronta or fingerprint (ieui oset abe* pcco) given for an edition attributed to Besicken around 1504 in the online version of the Censimento nazionale delle edizioni italiane del XVI secolo (EDIT16), the Italian national census of 16th-century printed books [EDIT 16 (2. ed.): CNCE 18284]. This and the other Besicken editions, however, seem to differ from our booklet in the leaf signatures [with the only exception of the edition described in GW 1803 (ISTC ia00682000)], the typesettings of the initial captions, incipits, and explicits. Moreover, the Gothic type used in our edition, measuring 86 mm. per 20 lines, and with characteristic capital letters A, F, M and Q, among other features, can be identified with Eusebius Salber’s 92 G [P. 6] rather than Johann Besicken’s 87 G.a [P. 1], which is close but not identical (see BM 15th cent., IV, 103 and 138, and pls X* and XII*). This type was also used in an edition of the Translatio ![Inc.7.B.2.27[3651], item 1, [a2]r - reduced and cropped](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Inc.7.B.2.273651-item-1-a2r-reduced-and-cropped.jpg) miraculosa ecclesiae Beatae Virginis Mariae de Loreto, a copy of which is Cambridge University Library (or CUL) Inc.7.B.2.27[3651], which has been attributed to Silber in most catalogues, including Oates’s, and dated to around 1500 in Sander 4292, and to after 1500 in Oates 1566, ISTC it00426500, GW M17565, and EDIT 16 (2. ed.), and CNCE 64630. Finally, the iconography of the initial woodcut in the Modus confitendi booklet seems to matches only that in the edition described in GW 1800 (ISTC ia00680000; Sander 363). After careful comparison of our text and woodcut with the descriptions of early 16th-century editions of Escobar’s work in GW and Sander, I tentatively identified our booklet (see Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 4) with an edition attributed to Eucharius Silber and dated to around 1498 by Sander but after 1500 in GW (GW 179510N), of which only one other exemplar seemingly survives. This other copy was described by Giuseppe Martini of Lugano in one of his catalogues [Cat. 28 (1938), no. 35] and afterwards by H. P. Kraus of New York [Cat. 83 (1957), no. 6]. I was however unable to find the present whereabouts of the Martini/Krauss copy and could not therefore confirm the identification.

miraculosa ecclesiae Beatae Virginis Mariae de Loreto, a copy of which is Cambridge University Library (or CUL) Inc.7.B.2.27[3651], which has been attributed to Silber in most catalogues, including Oates’s, and dated to around 1500 in Sander 4292, and to after 1500 in Oates 1566, ISTC it00426500, GW M17565, and EDIT 16 (2. ed.), and CNCE 64630. Finally, the iconography of the initial woodcut in the Modus confitendi booklet seems to matches only that in the edition described in GW 1800 (ISTC ia00680000; Sander 363). After careful comparison of our text and woodcut with the descriptions of early 16th-century editions of Escobar’s work in GW and Sander, I tentatively identified our booklet (see Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 4) with an edition attributed to Eucharius Silber and dated to around 1498 by Sander but after 1500 in GW (GW 179510N), of which only one other exemplar seemingly survives. This other copy was described by Giuseppe Martini of Lugano in one of his catalogues [Cat. 28 (1938), no. 35] and afterwards by H. P. Kraus of New York [Cat. 83 (1957), no. 6]. I was however unable to find the present whereabouts of the Martini/Krauss copy and could not therefore confirm the identification.

Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 5:

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 5, [a10]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-5-a10r-reduced1.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 5, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-5-a1r-reduced1.jpg)

The fifth item in our Sammelband is an edition of [Andreas de Escobar],

Interrogationes et doctrinae, also attributed by Oates (Oates 1571) to Besicken after 1500 [Images: leaves [a1] recto and [a10] recto]. Comparing our copy with editions of the work in ISTC and GW and with the annals of the Roman press of Eucharius and Marcellus Silber published by Alberto Tinto in 1968, I came to the conclusion that the booklet should perhaps be assigned to the Sibler press rather than Johann Besicken and could possibly be identified with the edition printed by Marcellus Silber around 1515 ( see

Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 5). A second copy of the edition held in the library, F150.e.2.7, had previously been identified with [Rome : Eucharius Silber, ca. 1495].

Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 7:

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 7, [a4]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-7-a4r-reduced.png)

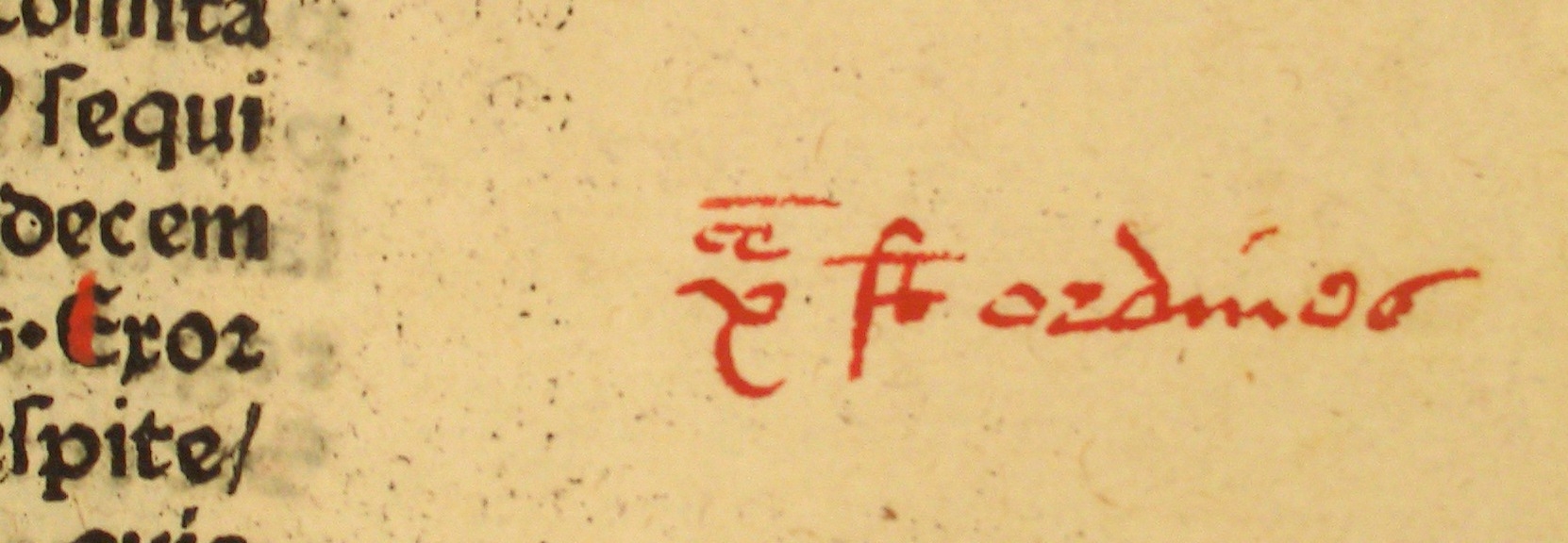

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 7, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-7-a1r-reduced.png) Item no. 7 is a copy of the Divisiones decem nationum totius Christianitatis and had not been catalogued in Newton before. The brief Oates’s note assigned it to Besicken and dated to after 1500 [Images: leaves [a1] recto and [a4] recto]. Indeed its textual features and impronta agree with those found in an edition attributed to Johann Besicken around 1505 in the online version of EDIT16 [EDIT 16 (2. ed.): CNCE 17304]. However, the type used, which measures 86 mm. per 20 lines, is once again closer to Eucharius Silber’s 92 G [P. 6] rather than to any of the different states of Johann Besicken’s 87 G.a [P. 1] as represented in CUL and British Library copies of the editions discussed by Paolo Veneziani and Martin Davies in their articles on Besicken and his successor Etienne Guillery. Moreover, the setting of the text seems to match an edition attributed to Eucharius Silber around 1491-1495 in GW 857010N and ISTC id00288200, of which only one copy is known to survive in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. GW gives the type of the edition as 86 G [P. 6*], matching the measures of the type in our book. I would therefore be inclined to follow GW and ISTC and identify our booklet as another copy of this rare edition (see Dd.5.60.G, item no 7).

Item no. 7 is a copy of the Divisiones decem nationum totius Christianitatis and had not been catalogued in Newton before. The brief Oates’s note assigned it to Besicken and dated to after 1500 [Images: leaves [a1] recto and [a4] recto]. Indeed its textual features and impronta agree with those found in an edition attributed to Johann Besicken around 1505 in the online version of EDIT16 [EDIT 16 (2. ed.): CNCE 17304]. However, the type used, which measures 86 mm. per 20 lines, is once again closer to Eucharius Silber’s 92 G [P. 6] rather than to any of the different states of Johann Besicken’s 87 G.a [P. 1] as represented in CUL and British Library copies of the editions discussed by Paolo Veneziani and Martin Davies in their articles on Besicken and his successor Etienne Guillery. Moreover, the setting of the text seems to match an edition attributed to Eucharius Silber around 1491-1495 in GW 857010N and ISTC id00288200, of which only one copy is known to survive in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. GW gives the type of the edition as 86 G [P. 6*], matching the measures of the type in our book. I would therefore be inclined to follow GW and ISTC and identify our booklet as another copy of this rare edition (see Dd.5.60.G, item no 7).

Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 8:

It seems to me that the same type was also used for the printing of the book that follows as item 8, a copy of [Petrus Georgii Tolomei], Translatio miraculosa ecclesiae Beatae Virginis Mariae de Loreto [Images: leaves [a1] recto, [a1] verso, and [a4] recto].

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 8, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-8-a1r-reduced.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 8, [a4]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-8-a4r-reduced1.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 8, [a1]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-8-a1v-reduced.jpg) The edition was assigned by Oates to Besicken after 1500 and indeed the text setting and the woodcut of the Virgin and Child (surrounded by sun rays, the Virgin standing on the crescent, all within a decorated border made of eight blocks, at the four corners the Virgin, the Archangel Gabriel, and two prophets, with the “B” of Besicken’s and Martinus de Amsterdam’s device at centre of the lower border) are recorded by Sander 4296 in an edition attributed by him to Besicken and Martinus de Amsterdam and dated to after 1500. Indeed the impronta in our booklet (ura- eruo nao- tane) corresponds to that recorded in the online EDIT 16 (CNCE 36420) for an edition assigned to Besicken to around 1504. Moreover, the woodcut is identical to one used by Besicken and Martinus in an edition of the German translation of the (Mirabilia Romae vel potius) Historia et descriptio urbis Romae dated 1500 in ISTC and more precisely to not before 11 August 1500 in GW (see ISTC im00609700, with link to BSB-Ink I-160 as well, and GW M23630). The edition of the Translatio recorded by Sander has been variously assigned in the other repertories as follows: to [Rome: Eucharius Silber, ca. 1500?] in Goff T426 followed by ISTC it00426000, to [Johann Besicken, after 1500] in IGI V p. 208, and to [Johann Besicken, ca. 1504] in Floriano Grimaldi (ed.), Il libro lauretano : secoli XV-XVIII, Loreto, 1994, p. 75, no. 18, followed by the online EDIT 16 (CNCE 36420), whereas GW M17557 only vaguely assigned it to Rome. In the face of such uncertainty and on the basis of the use of the 86 G type, generally assigned to Silber, I decided, for the time being, to follow Goff and ISTC and assign the edition to Eucharius Silber and to around 1500 while I continue to assess the matter, see Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 8.

The edition was assigned by Oates to Besicken after 1500 and indeed the text setting and the woodcut of the Virgin and Child (surrounded by sun rays, the Virgin standing on the crescent, all within a decorated border made of eight blocks, at the four corners the Virgin, the Archangel Gabriel, and two prophets, with the “B” of Besicken’s and Martinus de Amsterdam’s device at centre of the lower border) are recorded by Sander 4296 in an edition attributed by him to Besicken and Martinus de Amsterdam and dated to after 1500. Indeed the impronta in our booklet (ura- eruo nao- tane) corresponds to that recorded in the online EDIT 16 (CNCE 36420) for an edition assigned to Besicken to around 1504. Moreover, the woodcut is identical to one used by Besicken and Martinus in an edition of the German translation of the (Mirabilia Romae vel potius) Historia et descriptio urbis Romae dated 1500 in ISTC and more precisely to not before 11 August 1500 in GW (see ISTC im00609700, with link to BSB-Ink I-160 as well, and GW M23630). The edition of the Translatio recorded by Sander has been variously assigned in the other repertories as follows: to [Rome: Eucharius Silber, ca. 1500?] in Goff T426 followed by ISTC it00426000, to [Johann Besicken, after 1500] in IGI V p. 208, and to [Johann Besicken, ca. 1504] in Floriano Grimaldi (ed.), Il libro lauretano : secoli XV-XVIII, Loreto, 1994, p. 75, no. 18, followed by the online EDIT 16 (CNCE 36420), whereas GW M17557 only vaguely assigned it to Rome. In the face of such uncertainty and on the basis of the use of the 86 G type, generally assigned to Silber, I decided, for the time being, to follow Goff and ISTC and assign the edition to Eucharius Silber and to around 1500 while I continue to assess the matter, see Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 8.

Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 9:

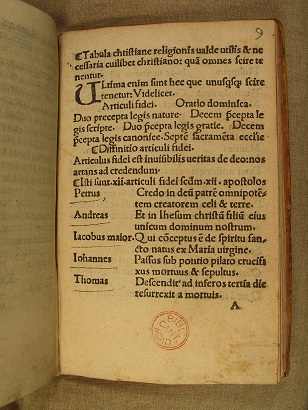

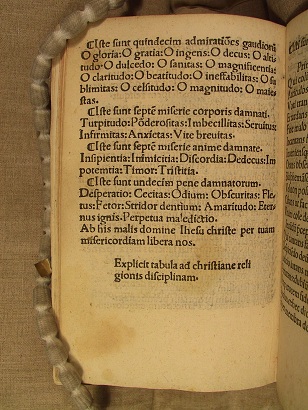

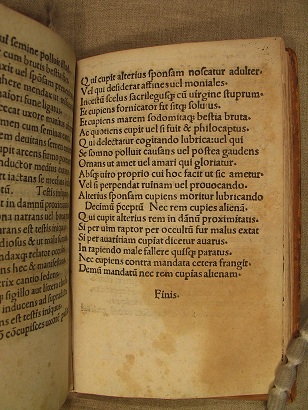

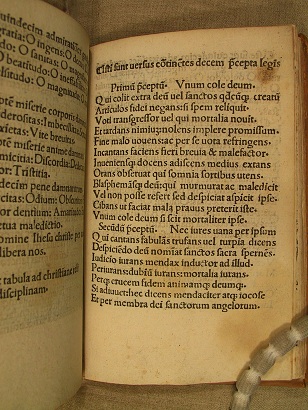

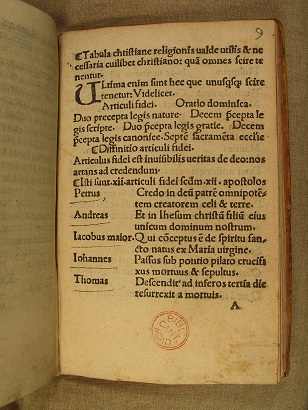

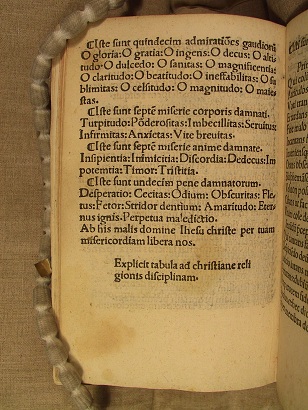

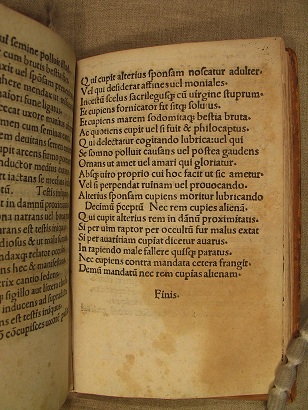

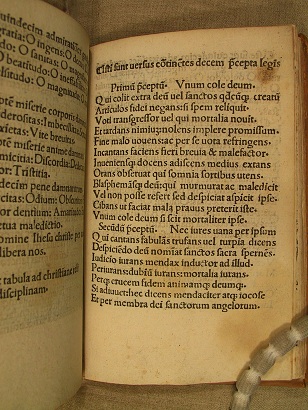

The ninth item, a copy of the Tabula christianae religionis, including at the end a short text entitled Decem praecepta legis, is the only booklet in the volume that was assigned to Eucharius Silber by Oates. Indeed the Roman type used for this edition is very close to Silber’s 84 R (P. 8), which was in use perhaps in 1493 and certainly in 1495-1500 (see BMC, IV, p. 103), and measures 85 mm. per 20 lines. This is the type recorded in GW M44694 for an edition assigned to Silber, which also shows the same text setting, number of leaves, leaf signatures, and number of lines to the page of our booklet. I would therefore be inclined to identify our edition with this

The ninth item, a copy of the Tabula christianae religionis, including at the end a short text entitled Decem praecepta legis, is the only booklet in the volume that was assigned to Eucharius Silber by Oates. Indeed the Roman type used for this edition is very close to Silber’s 84 R (P. 8), which was in use perhaps in 1493 and certainly in 1495-1500 (see BMC, IV, p. 103), and measures 85 mm. per 20 lines. This is the type recorded in GW M44694 for an edition assigned to Silber, which also shows the same text setting, number of leaves, leaf signatures, and number of lines to the page of our booklet. I would therefore be inclined to identify our edition with this

rare Silber edition, of which GW records only one copy in the Staatsbibliothek of Berlin. The German catalogue, however, does not provide any indication or suggestion for the date of printing, and I would therefore be most grateful for any suggestion or further information (see Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 9). [Images: leaves A1 recto, B7 verso, B8 recto and B10 recto].

rare Silber edition, of which GW records only one copy in the Staatsbibliothek of Berlin. The German catalogue, however, does not provide any indication or suggestion for the date of printing, and I would therefore be most grateful for any suggestion or further information (see Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 9). [Images: leaves A1 recto, B7 verso, B8 recto and B10 recto].

:

:

Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 10:

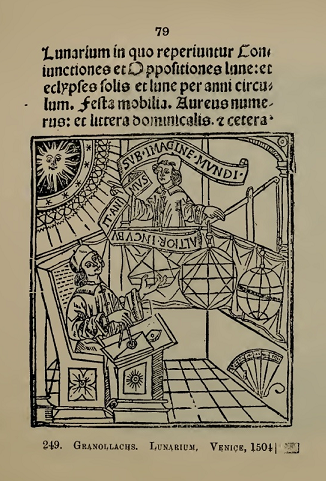

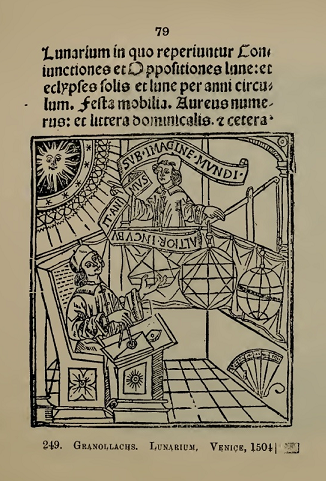

The last booklet in the volume, a copy of Bernardus de Granollachs’s Lunarium from 1504 to 1550, is apparently even rarer [Images: leaves [a1] recto, [a1] verso, [a2] recto, [a2] verso, and c8 verso]![Dd.5.60.G, no. 10, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-10-a1r-reduced.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 10, [a2]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-10-a2r-reduced.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 10, [a1]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-10-a1v-reduced.jpg) It was attributed to [Rome : Johannes Besicken, 1504] in Adams, vol. I, p. 499, no. G 1000, and simply to [Rome : 1504] by Oates. Being an early 16th-century book, this edition is ignored by both ISTC and GW. The woodcut on

It was attributed to [Rome : Johannes Besicken, 1504] in Adams, vol. I, p. 499, no. G 1000, and simply to [Rome : 1504] by Oates. Being an early 16th-century book, this edition is ignored by both ISTC and GW. The woodcut on  leaf [a1] recto is identical to the one that first appeared in an edition of the Lunarium for the years 1494-1550 attributed to [Rome: Johann Besicken, 1493-94] by ISTC ig00343500, to [Rome: Johann Sigismund Besicken, ca. 1494] by Sander 3228, and to [Rome: Johann Sigismund Besicken and Mayr, 1494] by BSB-Ink G-242 (with electronic facsimile). The same woodcut was also used to illustrate four editions of the Lunarium for the years 1497-1550, most of which were attributed to Plannk by Sander (see Sander 3232-3235). Searching the web, as one does now-a-days, I found an edition of the Lunarium from 1504 to 1550 listed as no. 249 in a Bernard Quaritch’s catalogue, A Catalogue of Early Printed Books Illustrated with Woodcuts …, London, no. 353, May 1919, p. 54, no. 249, pl. 79 (offered for sale at £ 6.10.0). The two booklets were printed with similar types but with a slightly different setting, as clearly shown by the reproductions of their title pages (in the Quaritch edition, the conjunction “et” is spelled out and the word “Littera” begins with a capital). The two books are therefore either two different issues of the same edition or two different editions altogether. The Quaritch catalogue suggested a Venetian origin for its Granollachs edition. The Gothic type used in our book measures 64 mm. per 20 lines and is similar but not identical to type 60 G [P. 2] used by Johann Besicken (cfr. BM 15th cent., IV, 138). It does not match the Gothic type G 66 used by Eucharius Silber in the edition of [Alfonso de Soto. Glossa in Regulas Cancellarie Innocentii VIII, cum textu] dated 6 June 1504 and reproduced in Tinto, p. II, either. In fact, it does not resemble any of the types recorded in BM 15th century for Besicken, Silber, or Plannk (the latter published at least 8 editions of Granollach’s Lunarium between 1487 and 1500). In addition, the impronta in our book (i.n- E.is .Gis Iuxx, if I am not mistaken), differs from that registered for an edition of the Lunarium attributed to Besicken in 1504 in online EDIT 16 (CNCE 21579, for which the impronta is given as: s.do s.is s.us Iuma): this edition survives in two copies, respectively in the Biblioteca comunale Ariostea at Ferrara and the Biblioteca universitaria at Pisa. It should be noted that the only reference provided by EDIT 16 is Adams, no. G1000, i.e. our booklet, which makes me wonder whether the compiler of EDIT 16 ever bothered to compare their copies with ours! All these conflicting factors leave me with many unanswered questions and I have therefore provisionally attributed this last small booklet to [Rome ? : ca. 1504] (see Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 10), following, in fact, what Oates said in the first instance !

leaf [a1] recto is identical to the one that first appeared in an edition of the Lunarium for the years 1494-1550 attributed to [Rome: Johann Besicken, 1493-94] by ISTC ig00343500, to [Rome: Johann Sigismund Besicken, ca. 1494] by Sander 3228, and to [Rome: Johann Sigismund Besicken and Mayr, 1494] by BSB-Ink G-242 (with electronic facsimile). The same woodcut was also used to illustrate four editions of the Lunarium for the years 1497-1550, most of which were attributed to Plannk by Sander (see Sander 3232-3235). Searching the web, as one does now-a-days, I found an edition of the Lunarium from 1504 to 1550 listed as no. 249 in a Bernard Quaritch’s catalogue, A Catalogue of Early Printed Books Illustrated with Woodcuts …, London, no. 353, May 1919, p. 54, no. 249, pl. 79 (offered for sale at £ 6.10.0). The two booklets were printed with similar types but with a slightly different setting, as clearly shown by the reproductions of their title pages (in the Quaritch edition, the conjunction “et” is spelled out and the word “Littera” begins with a capital). The two books are therefore either two different issues of the same edition or two different editions altogether. The Quaritch catalogue suggested a Venetian origin for its Granollachs edition. The Gothic type used in our book measures 64 mm. per 20 lines and is similar but not identical to type 60 G [P. 2] used by Johann Besicken (cfr. BM 15th cent., IV, 138). It does not match the Gothic type G 66 used by Eucharius Silber in the edition of [Alfonso de Soto. Glossa in Regulas Cancellarie Innocentii VIII, cum textu] dated 6 June 1504 and reproduced in Tinto, p. II, either. In fact, it does not resemble any of the types recorded in BM 15th century for Besicken, Silber, or Plannk (the latter published at least 8 editions of Granollach’s Lunarium between 1487 and 1500). In addition, the impronta in our book (i.n- E.is .Gis Iuxx, if I am not mistaken), differs from that registered for an edition of the Lunarium attributed to Besicken in 1504 in online EDIT 16 (CNCE 21579, for which the impronta is given as: s.do s.is s.us Iuma): this edition survives in two copies, respectively in the Biblioteca comunale Ariostea at Ferrara and the Biblioteca universitaria at Pisa. It should be noted that the only reference provided by EDIT 16 is Adams, no. G1000, i.e. our booklet, which makes me wonder whether the compiler of EDIT 16 ever bothered to compare their copies with ours! All these conflicting factors leave me with many unanswered questions and I have therefore provisionally attributed this last small booklet to [Rome ? : ca. 1504] (see Dd*.5.60(G), item no. 10), following, in fact, what Oates said in the first instance !

Working on this volume faced me with some difficult questions of attribution. It also brought to my mind many other questions regarding how to convey bibliographical information in the most effective way in our catalogue despite the constraints of the international rules for cataloguing rare books. The rules, for instance, discourage “diplomatic” transcription of texts; it was only through the comparison of the diplomatic transcriptions of the initial captions in other repertories, however, that I could separate and identify the different editions of the texts gathered in our sammelbound. The natural conclusion is that any online cataloguing project relating to rare books should aim to include the digitisation of the material when not already digitised elsewhere or unique, and link the bibliographical descriptions to a few relevant images (incipits, explicits, woodcut decoration, hand decoration and binding). As Paul Needham put it, “Lengthy … narratives rarely provide usable information … good reproductions always do” !

Bibliography:

H. M. Adams, Catalogue of books printed on the Continent of Europe, 1501-1600 in Cambridge Libraries, 2 vols, London, 1967.

Catalogue of books printed in the XVth century now in the British Museum [British Library], 13 parts, London, 1963-2007.

Martin C. Davies, “Besicken and Guillery”, in The Italian book 1465-1800, Studies presented to Dennis E. Rhodes on his 70th birthday, edited by Denis V. Reidy, London, 1993, 35-54.

Paul Needham, “Copy Description in Incunable Catalogues”, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 95 (2001), 173-239.

Paul Needham, “The Bodleian Library Incunables”, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 101.3 (2007), 345-395.

J.C.T. Oates, A catalogue of the fifteenth-century printed books in the University Library Cambridge, Cambridge, 1954.

Vera Sack, Die Inkunabeln der Universitätsbibliothek und anderer öffentlicher Sammlungen in Freiburg im Breisgau und Umgebung, 3 vols, Wiesbaden, 1985.

Max Sander, Le Livre a Figures Italien depuis 1467 jusqu’a 1530, 6 vols, Milan, [1942-43]; with Supplement by Carlo Enrico Rava, Milano, 1969.

Alberto Tinto, Gli annali tipografici di Eucario e Marcello Silber (1501-1527), Firenze, 1968 (Bibli.oteca di bibliografia italiana, 55).

Paolo Veneziani, “Besicken e il metodo degli incunabolisti”, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 2005, 77-99.

![Inc.1.A.2.3[84], f. [215]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.2.384-f.-215v-reduced3.jpg)

![Inc.1.A.1.1[3761], 2, [y6]v - first mark](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.1.13761-2-y6v-first-mark3.jpg)

![Inc.1.A.2.3[84], f. [215]v - first line](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.2.384-f.-215v-first-line3.jpg)

![Inc.1.A.1.1[3761], 2, [y7]r - second mark](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.1.13761-2-y7r-second-mark3.jpg)

![Inc.1.A.2.3[84], f. [215]v - last line](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Inc.1.A.2.384-f.-215v-last-line1.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a1]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a1v-reduced.png)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a1r-reduced.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a5]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a5v-reduced.png)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a7]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a7v-reduced.png)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 6, [a6]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-6-a6r-reduced1.png)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 4, [a1]r, detail - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-4-a1r-detail-reduced4.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 4, [b4]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-4-b4r-reduced7.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 4, [a1]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-4-a1v-reduced4.jpg) Indeed, our booklet shows the same number of leaves and lines, i.e. 12 leaves with 23 lines to the page, as the editions of this text assigned to Besicken in

Indeed, our booklet shows the same number of leaves and lines, i.e. 12 leaves with 23 lines to the page, as the editions of this text assigned to Besicken in ![Inc.7.B.2.27[3651], item 1, [a2]r - reduced and cropped](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Inc.7.B.2.273651-item-1-a2r-reduced-and-cropped.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 5, [a10]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-5-a10r-reduced1.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 5, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-5-a1r-reduced1.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 7, [a4]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-7-a4r-reduced.png)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 7, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Dd.5.60.G-no.-7-a1r-reduced.png)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 8, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-8-a1r-reduced.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 8, [a4]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-8-a4r-reduced1.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 8, [a1]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-8-a1v-reduced.jpg) The edition was assigned by Oates to Besicken after 1500 and indeed the text setting and the woodcut of the Virgin and Child (surrounded by sun rays, the Virgin standing on the crescent, all within a decorated border made of eight blocks, at the four corners the Virgin, the Archangel Gabriel, and two prophets, with the “B” of Besicken’s and Martinus de Amsterdam’s device at centre of the lower border) are recorded by Sander 4296 in an edition attributed by him to Besicken and Martinus de Amsterdam and dated to after 1500. Indeed the impronta in our booklet (ura- eruo nao- tane) corresponds to that recorded in the online EDIT 16 (CNCE 36420) for an edition assigned to Besicken to around 1504. Moreover, the woodcut is identical to one used by Besicken and Martinus in an edition of the German translation of the (Mirabilia Romae vel potius) Historia et descriptio urbis Romae dated 1500 in ISTC and more precisely to not before 11 August 1500 in GW (see

The edition was assigned by Oates to Besicken after 1500 and indeed the text setting and the woodcut of the Virgin and Child (surrounded by sun rays, the Virgin standing on the crescent, all within a decorated border made of eight blocks, at the four corners the Virgin, the Archangel Gabriel, and two prophets, with the “B” of Besicken’s and Martinus de Amsterdam’s device at centre of the lower border) are recorded by Sander 4296 in an edition attributed by him to Besicken and Martinus de Amsterdam and dated to after 1500. Indeed the impronta in our booklet (ura- eruo nao- tane) corresponds to that recorded in the online EDIT 16 (CNCE 36420) for an edition assigned to Besicken to around 1504. Moreover, the woodcut is identical to one used by Besicken and Martinus in an edition of the German translation of the (Mirabilia Romae vel potius) Historia et descriptio urbis Romae dated 1500 in ISTC and more precisely to not before 11 August 1500 in GW (see

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 10, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-10-a1r-reduced.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 10, [a2]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-10-a2r-reduced.jpg)

![Dd.5.60.G, no. 10, [a1]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Dd.5.60.G-no.-10-a1v-reduced.jpg)

![Inc.1.B.3.1b[1341], [a2]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.B.3.1b1341-a2r-reduced.jpg)

![Inc.1.B.3.1b[1341], My lord chancellor - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.B.3.1b1341-My-lord-chancellor-reduced.png)

![Inc.1.B.3.1b[1341], [x5]r, Moore's annotation - detail - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.B.3.1b1341-x5r-Moores-annotation-detail-reduced.png)

![Inc.1.B.3.1b[1340], [a2]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.B.3.1b1340-a2r-reduced.jpg)

![Inc.5.B.2.5[1147]](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.5.B.2.51147-a1r-reduced-blog2.jpg)

![Inc.7.B.2.26[1270], [a2]v - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.7.B.2.261270-a2v-reduced.png)

![Inc.7.B.2.26[1270], Virgin and Child - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.7.B.2.261270-Virgin-and-Child-reduced.png)

![Inc.7.B.2.26[1270], [a3]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.7.B.2.261270-a3r-reduced1.png)

![Inc.7.B.2.26[1270], [a3]r - inscription detail - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.7.B.2.261270-a3r-inscription-detail-reduced2.png)

![Inc.5.B.3.2[1363], a1r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.5.B.3.21363-a1r-reduced.jpg)

![Inc.5.B.3.2[1363], Webbe's inscription - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.5.B.3.21363-Webbes-inscription-reduced.png)

![Inc.5.B.3.2[1363], lower cover - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.5.B.3.21363-lower-cover-reduced.jpg)