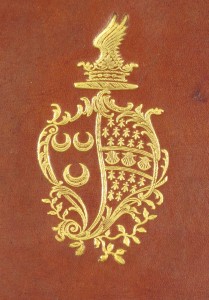

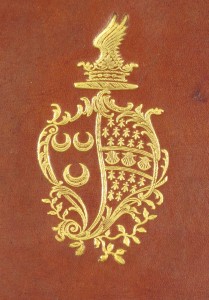

The Library of Michael Wodhull (1740-1816), Dibdin’s ‘Orlando’, poet and the first translator into English of the extant works of Euripides, is well-known. His books are immediately recognisable, either through his distinctive gilt armorial device, or from his equally distinctive annotations. The history of his collection is succinctly described in de Ricci’s English Collectors of Books & Manuscripts. Wodhull haunted the London sale rooms between 1764 and 1815, amassing a remarkable collection of early-printed books, many of which he subsequently had bound by Roger Payne.

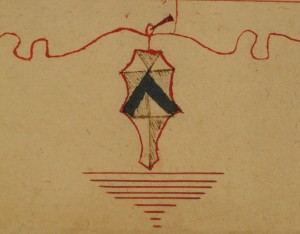

Wodhull's gilt armorial stamp on the binding of SSS.4.16

After Wodhull’s demise, appropriately enough within the Library he created at Thenford, his books passed first to his sister, Mary Ingram, from her to Samuel Amy Severne and then to J.E. Severne, who auctioned the collection at Sotheby’s in 1886. During his lifetime Wodhull disposed of a number of duplicates, and books from these sales can be clearly identified from his habit of excising the upper corner of the front flyleaf, removing evidence of the date and price of purchase.

Although famed for its classical incunabula, Wodhull’s library was diverse. The Incunabula Cataloguing Project has to date recorded 21 fifteenth-century books from his collection, amongst which is an intriguing volume containing two legal texts; Vocabularius juris utriusque ([Basel : Michael Wenssler, between 1475 and 1478] – ISTC iv00335600 ), the law dictionary compiled by Jodocus Erfordensis (fl. ca. 1452), and Maffeo Vegio’s Vocabula ex iure civili excerpta (Vicenza: Philippus Albinus, 1 Dec. 1477 – ISTC iv00122000).

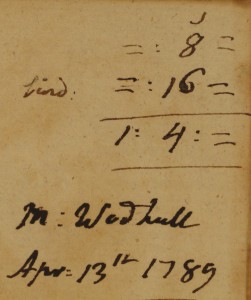

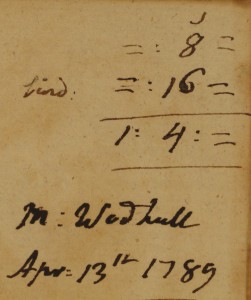

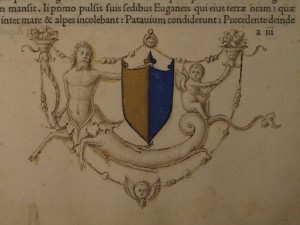

Wodhull's annotations to the front flyleaf of SSS.4.16

Wodhull’s ever-helpful annotations demonstrate that the two items were formerly in the monumental Venetian library of the director of the official Venetian press, Maffeo Pinelli (1736-1785), brought to England by the bookseller James Edwards (1757-1816) and sold by auction on 2 March 1789 and 1 February 1790. Wodhull acquired the book for the bargain price of 8s, then paid a further 16s to have it bound. The catalogue of the Pinelli sale confirms this; item 6016:

“Vocabularius Juris utriusque, Absque ulla nota, Sæc. XV. fol.- Editio pervetusta est, sine numeris, signaturis, & custodibus, character Germanico, eoque rudi.

Vegii Liber Vocabulorum ex Jure Civili excerptorum, Vincentiæ, MCCCLXXVII, fol.”

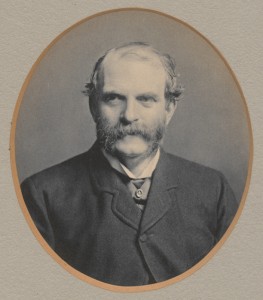

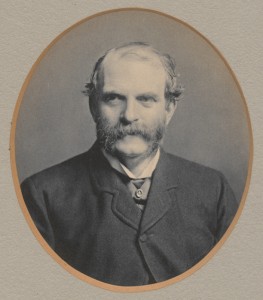

At the 1886 Wodhull sale the volume was item 2730, described there as having “MS. notes and initials historiated with drawings”, a “fine copy in russia by Mrs. Weir”. It sold for £1:15s to the bookseller Bennett, who then offered it as item 228 in an as yet unidentified catalogue, listed under ‘Early Printing’ – “A capital specimen of early printing in Black Letter … finely bound in russia gilt, rough edges, by Mrs. Weir.” From Bennett it went to the great collector and benefactor of Cambridge University Library, Samuel Sandars (1837-1894), bequeathed to the Library in 1894.

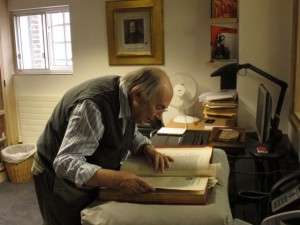

Samuel Sandars (1837-1894)

The attribution of the binding to Mrs Weir is intriguing – I can find little written on either Mrs Weir (sometimes Wier) or her husband, David (possibly Richard?), assistants in Payne’s bindery in the 1770s, and would welcome leads on more information. The earliest printed reference I can find to the Weirs is in Dibdin’s Bibliographical Decameron, where he states that the husband and wife worked together in Toulouse, repairing and binding books for Count Justin MacCarthy-Reagh (1744-1811) before working for Payne. Charles Ramsden confirms the Toulouse connection, convincingly showing that the Weirs spent at least three years with MacCarthy-Reagh, although there is some discrepancy around the precise dates – Ramsden 1771-1774, Dibdin 1774-1777 – and his attribution of a group of bindings to MacCarthy-Reagh and then to Weir remains hypothetical.[1] Dibdin further notes that Mrs Weir undertook repair work for Payne, then later “betook herself to Edinburgh”, repairing the books and documents at Edinburgh Record Office.[2] The Jaffray MSS confirm this move to Edinburgh: “She went down to repair, wash and mend the MSS. of the Society of Writers to the Signet in Edinburgh at a salary of £1.1.0 a week, where she died.”[3]

Portrait of Mrs Weir, from Dibdin's 1817 'Bibliographical Decameron', volume 2, p. 518

Cyril Davenport’s Roger Payne gives a sketchy account of the activities of both Weirs, identifying Mrs Weir as “a very skilful repairer of old books and paper” and concluding “Certainly one or two bindings credited to Payne were not done by him at all but by the Weirs … The great test is the quality of the gilding … Payne’s … is brilliant; Weir’s … is not so clear and smooth.”[4] Bernard Middleton notes Mrs Weir as “renowned as a paper-mender” and cites a single unidentified binding signed ‘Bound by Weir’, supplementing the corpus of three identified by Ramsden and one further Storer Bequest binding identified by Mirjam Foot.[5]

Mirjam’s ODNB entry for Payne is more enlightening, but again restricts Mrs Weir’s activities to paper repairs and red-ruling:

“Both David Wier and his wife appeared to have worked for Payne. Mrs Wier, who apparently was a capable mender and restorer as well as ‘an excellent hand at ruling red … lines on prayer books’ (Jaffray, 4.182), was, according to Dibdin, ‘pretty constantly and most successfully employed’ (Dibdin, 517) by him, probably before 1774, while her husband (according to the same source) worked for Payne from 1777. The partnership was not a happy one—‘Wier happened to be as fond of “barley broth” as his associate … They were always quarrelling’ (ibid., 515)—and they parted company.”[6]

There is no doubt that David (Richard) Weir bound books, despite the paucity of surviving signed examples, and more work is needed to clarify the relationship between the Weirs and MacCarthy-Reagh – a recent communication with Mirjam Foot suggests that the late Giles Barber had long planned to work on some intriguing-sounding archival material in Toulouse. Beyond bookseller’s descriptions, however, there seems to be no evidence at all to suggest that Mrs Weir also worked as a binder. There is nothing on the CUL book to indicate why it was attributed to her in 1886, but it is worth noting that attributions to the Weirs seem to have been in vogue in the 1880s. Quaritch’s catalogue 93, Bookbinding, November 1888, for example contains sections dedicated to ‘Richard and Mrs. Wier’, and to ‘Bindings said to be by Roger Payne; probably done by Richard Wier and Roger Payne in partnership’. I suspect a degree of bookseller’s verbiage – if one could get away with attributing a binding to Payne one could charge a premium, if not then citing the Weirs was the next best thing.

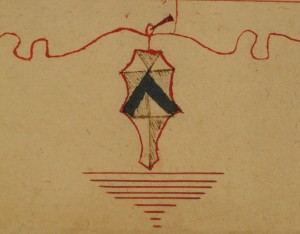

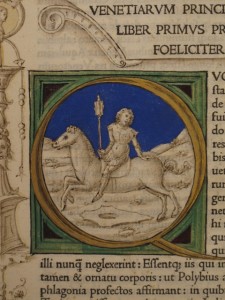

Unidentified armorial initial within SSS.4.16

Unidentified armorial device in SSS.4.16

The CUL volume raises other interesting questions around its pre-Pinelli history. The Vocabularius juris utriusque is rubricated throughout and has occasional fifteenth and sixteenth-century annotations and manicules in two hands. The Vegio, however, is unrubricated, but displays extensive fifteenth or early sixteenth-century annotations, corrections to the text, cross references, added entries and additional definitions in a very elegant hand, matching neither of those present in the Vocabularius. Clearly, on or soon after publication the books went separate ways. Both, however, share decorated initials in a style which suggests that they were brought together in the sixteenth century. The opening leaf of the Vocabularius bears two armorial devices, neither as yet identified (any help gratefully received). The first is contemporaneous with the decorated initials, the other much later, probably contemporaneous with the red-ruling of the leaf, the only leaf thus ruled.

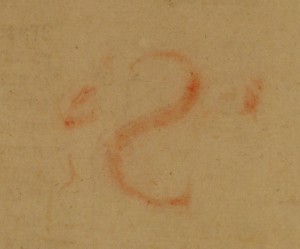

One final oddity – although bound in this order when Wodhull purchased the volume from the Pinelli sale, at some point in its history the volume appears to have been bound the other way round. There is a clear offset letter ‘S’ on the front flyleaf now facing the opening leaf of the Vocabularius, which matches exactly the decorated initial ‘S’ on the opening leaf of the Vegio, now the second bound item.

Decorative initial 'S' from SSS.4.16

Offset ink on the front flyleaf from the decorated initial 'S' now bound second

[1] Charles Ramsden ‘Richard Weir and Count MacCarthy-Reagh’ in

The Book Collector vol. 2, no. 4, winter 1953, pp. 247-257.

[2] Thomas Frognall Dibdin The Bibliographical Decameron (London: 1817) p. 518-9.

[3] Mirjam Foot The Henry Davis Gift … Volume I (London: 1978), p.110, footnote 53.

[4] Cyril Davenport Roger Payne (Chicago: Caxton Club, 1929) pp.22-24.

[5] Bernard Middleton A history of Englisg Cradt Bookbinding Technique (Delaware: 1996) pp. 207, 357; Charles Ramsden ‘Richard Weir and Count MacCarthy-Reagh’ in The Book Collector vol. 2, no. 4, winter 1953, pp. 253-4. Mirjam Foot The Henry Davis Gift … Volume I (London: 1978), p. 101.

[6] Mirjam M. Foot, ‘Payne, Roger (bap. 1738, d. 1797)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/21654, accessed 12 July 2012]

![Inc.0.A.7.2[888], fol. XCV verso - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Inc.0.A.7.2888-fol.-XCV-verso-reduced5-e1355403462857-244x300.jpg)