Pietro Bembo and the University Library copy of the De Aetna of 1496

Variants and corrections inserted in the Cambridge University Library copy of the Aldine edition of De Aetna (Inc.4.B.3.134[4580]) have been identified as autograph additions by the author of the text, the learnead Venetian humanist Pietro Bembo.

Pietro Bembo (1470-1547) was the most influential among 16th-century scholars for the future development of the Italian language and Italian literature. He wrote De Aetna, a fictitious dialogue between himself and his father Bernardo relating to Pietro’s trip to Mount Etna in Sicily during an eruption, while he was studying Greek with Konstantinus Lascaris. The book was published in Venice by Aldus Manutius in February 1495 more Veneto, i.e. 1496 (ISTC ib00304000; GW 3810). Its publication was important for three reasons: it is Bembo’s first Latin work, it is the first of his works to be put into print and it is the first Latin text printed by Aldus Manutius.

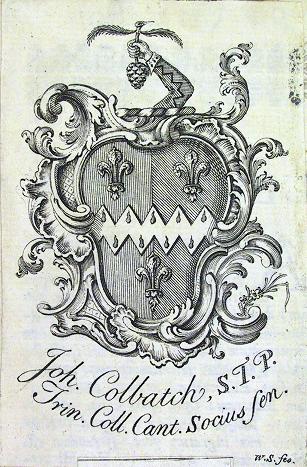

The University Library copy was formerly in the possession of Stanley Morison (1889-1967), the distinguished English typographer described as “Britain’s greatest authority on letter-design” in the Dictionary of National Biography.[1] ![Inc.4.B.3.134[4580], A1r - tondo - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Inc.4.B.3.1344580-A1r-tondo-blog.jpg) In 1928 Morison created the famous Bembo font from the Roman tondo used by Aldus for Bembo’s De Aetna. This was the fourth of the tondo typefaces designed and cut for Aldus Manutius by the Bolognese punchcutter Francesco Griffo who, for his part, had taken inspiration from the formal humanistic script of Renaissance Italian scribes.[2] Aldus used it for the first time to print De Aetna, which therefore scores another “record”.

In 1928 Morison created the famous Bembo font from the Roman tondo used by Aldus for Bembo’s De Aetna. This was the fourth of the tondo typefaces designed and cut for Aldus Manutius by the Bolognese punchcutter Francesco Griffo who, for his part, had taken inspiration from the formal humanistic script of Renaissance Italian scribes.[2] Aldus used it for the first time to print De Aetna, which therefore scores another “record”.

![Inc.4.B.3.134[4580], upper pastedown - Morison - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Inc.4.B.3.1344580-upper-pastedown-Morison-blog.jpg) Morison inscribed the upper pastedown of his copy with the note “Property of the Monotype Corporation to be preserved as being the original of Series 270 cut in & produced in matrix for in 1930 / Stanley Morison”. Morison had bought the book for £ 100 from Davis & Orioli in April 1940, therefore little more than 10 years after designing the Bembo font. Later on, at an unknown date, he donated it to the Monotype Corporation, which gave it to library in 1967, seven years after Morison’s death. The donation was most welcome to the library, not only because it filled a gap in the incunable collection, but also on account of the association with Stanley Morison and his work at Monotype.[3]

Morison inscribed the upper pastedown of his copy with the note “Property of the Monotype Corporation to be preserved as being the original of Series 270 cut in & produced in matrix for in 1930 / Stanley Morison”. Morison had bought the book for £ 100 from Davis & Orioli in April 1940, therefore little more than 10 years after designing the Bembo font. Later on, at an unknown date, he donated it to the Monotype Corporation, which gave it to library in 1967, seven years after Morison’s death. The donation was most welcome to the library, not only because it filled a gap in the incunable collection, but also on account of the association with Stanley Morison and his work at Monotype.[3]

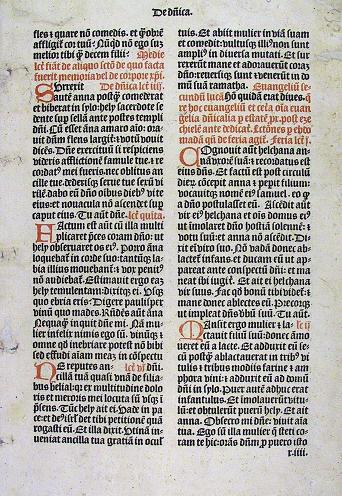

The book is important for another reason. It bears eight of the manuscript corrections discussed in a famous article entitled “Manuscript Corrections in the Aldine Edition of Bembo’s De Aetna” published in 1951 by Curt F. Bühler,[4] who did not know about the present book, then still the property of Monotype. The corrections have been washed away, but most of them can still be read by the naked eye as on leaves A8 verso and D2 verso.

As noted by Bühler and later by Bianca Maria Mariano in an article published in 1991,[5] they were all included in the second revised edition of the text published by the Venetian printer Johannes Antonius da Sabio and brothers in 1530.[6]

Furthermore, our book also shows a few additional marginal and interlinear corrections and additions that have not been noticed in the copies studied by Bühler: the substitution, for instance, of “segetes” for “fru-ges” on leaf B6 verso, lines 8-9,

the substitution of “inspectantibus” for “uidentibus” on leaf D2 recto, line 15,

and the insertion of the word “pater” above line 15 of leaf C7 recto.

All these changes can also be found in the 1530 edition.

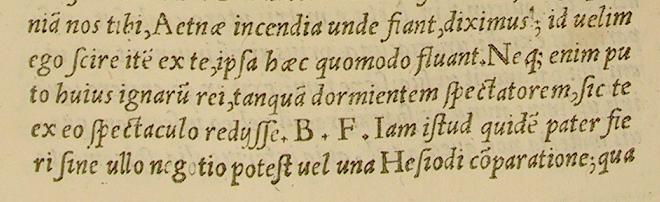

On the latter page a very faint two-line addition to the text has been supplied in the lower margin. With the help of UV light one can read “neq[ue] enim puto huius ignarum rei tamq[uam] dormientem / spectatorem sic te ex eo spectaculo redijsse” [i.e. “because I didn’t imagine you returned from the spectacle like a dozing spectator, with no knowledge of it !”].

The addition matches a variant that can be found on leaf B5 recto of the 1530 edition, leaf Bb5 recto.

Overall the text of the 1530 edition confirms that all the marginal notes, variants and corrections introduced manually to our book were authorial changes, that is to say they came from Bembo himself. According to Bühler, these notes and corrections were separately carried out on each book in Aldus’s shop at the time of its sale. This would explain the differences in the number of corrections appearing in different copies: some books have only a few, others have more as if mistakes were discovered and changes were carried out by the author as time went by. I briefly checked the copies of the 1495 edition held in the Bodleian Library and in the British Library. They also bear such manuscript corrections, most of them written by accomplished hands, but none by the same hand that we find in the Cambridge copy, with the possible exception of the annotations in incunable IA.24410, washed away and therefore requiring an UV light investigation.

I believe that the small and sharp, but educated and elegant humanistic cursive hand found in our copy is the hand of Pietro Bembo himself. The identification is confirmed, I believe, by the comparison with marginal notes in two manuscripts of Horace copied by Bartolomeo Sanvito for Bembo’s father, Bernardo, and now in the manuscript collections of King’s College Cambridge (MS. 34, fol. 149 verso) and of the University Library (MS. Dd.15.13, fol. 58 recto) .

The annotator of the two manuscripts has been identified as Pietro by Professor de la Mare and Massimo Danzi.[7]

Bembo is well known for always revising his works, constantly correcting and adding to them. I don’t think, however, that the Cambridge book is a personal working copy of the text: it is too clean, almost immaculate, and has no sign of use in a printing house. Moreover, the few marginal additions and corrections in the book are very far from the more than 150 variants registered in the 1530 edition by Mariano. I think that our book was given by Bembo to an unidentified individual shortly after publication and after he had carefully added his own corrections, variants and supplements to the text. Unfortunately the old parchment cover of the book has been heavily restored and the old endleaves disposed of, so that we have no indication of ownership or provenance before Morison. What remains to do, now, is to check again all the other 39 extant copies of the edition for traces of Bembo’s hand.

A fuller account of Bembo’s variant and corrections in our copy of the De Aetna can be found in L. Nuvoloni, “Bembo ritrovato : varianti e correzioni d’autore nel De Aetna aldino della University Library di Cambridge”, L’Ellisse. Studi storici di letteratura italiana, VI (2011), pp. 205-210, pls V-VIII.

[1] H. G. Carter, “Morison, Stanley Arthur (1889–1967)”, rev. David McKitterick, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35107, accessed 12 July 2012]

[2] P. Tinti, “Griffo (Grifi, Griffi), Francesco (Francesco da Bologna)”, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 59, Rome, 2003, pp. 377-380; http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-francesco-da-bologna-griffo_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/, for the online edn.

[3] A letter from Davis & Orioli to Stanley Morison, dated 4 December 1942, an advice note from the Monotype Corporation to Davis & Orioli, dated 10 October 1952, and a copy of the letter from the director of the University Library to J. Matson of The Monotype Corporation, dated 23 July 1974, are kept with the book.

[4] C. F. Bühler, “Manuscript Corrections in the Aldine Edition of Bembo’s De Aetna”, The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, XLV (1951), pp. 136-42.

[5] B. M. Mariano, “Il De Aetna di P. Bembo e le varianti dell’edizione 1530”, Aevum, 65 (1991), pp. 441-52.

[6] For the 1530 edition, see Catalogue of books printed on the continent of Europe, 1501-1600, in Cambridge libraries, compiled by H. M. Adams, London, 1967, p. 109, no. 584. Cambridge, University Library, F152.d.2.7, item no. 2.

[7] A.C. de la Mare, “Marginalia and Glosses in the Manuscripts of Bartolomeo Sanvito of Padua”, in Talking to the text: Marginalia from Papyri to Print. Proceedings of a Conference held at Erice 26 Sept.–3 Oct. 1998…, ed. V. Fera, G. Ferraù and S. Rizzo, Messina, 2002 [Percorsi dei classici, 5], vol. II, pp. 459-555 (466 n.1, 519, 521); M. Danzi, La biblioteca del Cardinale Pietro Bembo, Geneva, 2005, p. 336, pls 2-6 (pls 7-28 for images of Petro’s notes in other manuscripts); A. C. de la Mare and L. Nuvoloni, Bartolomeo Sanvito. The life and work of a Renaissance scribe, eds A. R. A. Hobson and C. de Hamel, Paris and Dorchester, 2009 (The Handwriting of the Italian Humanists, 2), nos 64, 82; M. Danzi, “Pietro Bembo”, in Autografi dei letterati italiani, vol. 3.1, Rome, 2009, pp. 47-59 (54).

![Inc.4.B.3.134[4580], A1r - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Inc.4.B.3.1344580-A1r-blog2.jpg)

![Inc.4.B.3.134[4580], D2v - detail - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Inc.4.B.3.1344580-D2v-detail-blog.jpg)

![Inc.4.B.3.134[4580], A8v - detail - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Inc.4.B.3.1344580-A8v-detail-blog.jpg)

![Inc.4.B.3.134[4580], B6v - detail - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Inc.4.B.3.1344580-B6v-detail-blog.jpg)

![Inc.4.B.3.134[4580], D2r - detail - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Inc.4.B.3.1344580-D2r-detail-blog.jpg)

![Inc.4.B.3.134[4580], C7r - detail pater - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Inc.4.B.3.1344580-C7r-detail-pater-blog.jpg)

![Inc.4.B.3.134[4580], C7r - detail inscription - blog](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Inc.4.B.3.1344580-C7r-detail-inscription-blog.jpg)

![Inc.5.B.7.10[4004], s1r - Franciscus de Prato](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Inc.5.B.7.104004-s1r-Franciscus-de-Prato.jpg)

![Inc.5.B.7.10[4004], t4v - Franciscus de Prato](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Inc.5.B.7.104004-t4v-Franciscus-de-Prato.jpg)