The First Thousand! – A post by William Hale and Laura Nuvoloni

On 16th March 2011 the Incunable Project Team (William Hale, Laura Nuvoloni and Ed Potten) catalogued its 1000th book and published the record in Newton, the Cambridge University Library online catalogue.

The palm for the 1000th book to be catalogued by the team is contended for by a Missale ad usum Sarum published in Westminster by Julian Notary and Jean Barbier for Wynkyn de Worde on 20 December 1498 and the Biblia latina published in Mainz by Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer on 14 August 1462. This small milestone adds nothing to the history of the two books, as each of them represents an important edition in its own right, the missal being the first printed in England, the Bible the earliest to bear the name of its printers and the printing date. The milestone nevertheless marks the publication of catalogue descriptions for more than a fifth of the incunable holdings of the library, a significant step in the progress of the Incunabula Project at almost exactly 1 year and 5 months from its effective initial date on 13th October 2009. With the cataloguing pace on the increase from month to month, the team is well on target for achieving the cataloguing of the circa 4,700 incunabula within the 5-year fixed term project.

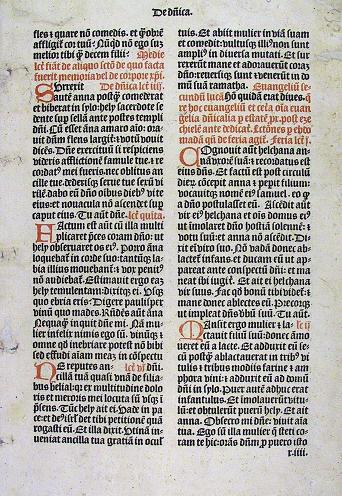

![Inc.3.J.1.3[3576], Sarum Missal, calendar - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.3.J.1.33576-Sarum-Missal-calendar-reduced.jpg) As a previous post by Ed Potten noted, early English editions of the Sarum liturgy were printed in Paris for English publishers. The Missal of 1498 (Inc.3.J.1.3[3576]) was commissioned by Caxton’s successsor Wynkyn de Worde; the actual printing was performed by two French expatriates: the Breton-born Julian Notary and Jean Barbier, about whom very little is known. The work called not only for printing throughout in red and black, but also for music notation. Printing of music was then in its very early stages and Notary and Barbier only provided the stave, leaving the notes to be filled in by hand if needed.

As a previous post by Ed Potten noted, early English editions of the Sarum liturgy were printed in Paris for English publishers. The Missal of 1498 (Inc.3.J.1.3[3576]) was commissioned by Caxton’s successsor Wynkyn de Worde; the actual printing was performed by two French expatriates: the Breton-born Julian Notary and Jean Barbier, about whom very little is known. The work called not only for printing throughout in red and black, but also for music notation. Printing of music was then in its very early stages and Notary and Barbier only provided the stave, leaving the notes to be filled in by hand if needed.

The missal bears an inscription recording its donation to the Chapel at Kew. This was a short-lived private chapel attached to Kew Farm, near the site of the present Palace, which was in existence only from 1522 to 1534. At a later date references to the pope and to St Thomas of Canterbury were crossed out, as is common in English liturgical books, the cult of St Thomas having been suppressed in 1538, four years after the Act of Supremacy placed Henry VIII at the head of the Church of England. In this case, the references were left sufficiently legible to be re-instated if the tide of religious reform should start to recede.

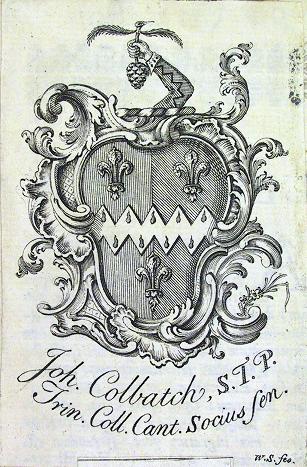

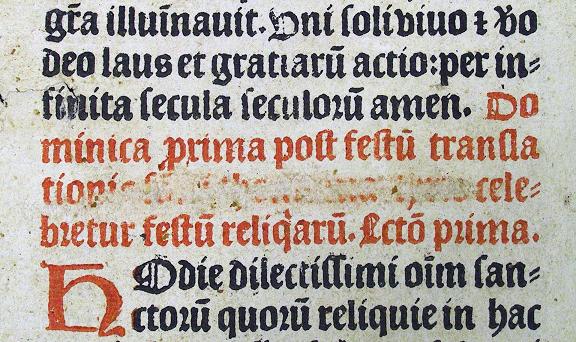

![Inc.3.J.1.3[3576], Sarum Missal, explicit - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.3.J.1.33576-Sarum-Missal-explicit-reduced.png) The book’s history during the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is unrecorded. In 1693 it was given by one “Arnold de Wycomb” to George Whitton. Whitton was a graduate of King’s College and native of Wycombe in Buckinghamshire who incorporated at Oxford in the same year he received the book; the unidentified Arnold is presumably a relative or family friend from the same place. The Missal must have passed into the collection of Bishop John Moore shortly after that date and would have reached the library with the remainder of the Bishop’s collection in 1715. It was probably given its rather workaday half-leather binding shortly afterwards.

The book’s history during the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is unrecorded. In 1693 it was given by one “Arnold de Wycomb” to George Whitton. Whitton was a graduate of King’s College and native of Wycombe in Buckinghamshire who incorporated at Oxford in the same year he received the book; the unidentified Arnold is presumably a relative or family friend from the same place. The Missal must have passed into the collection of Bishop John Moore shortly after that date and would have reached the library with the remainder of the Bishop’s collection in 1715. It was probably given its rather workaday half-leather binding shortly afterwards.

![Inc.1.A.1.3a[3762], I, [a1]r - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.1.A.1.3a3762-I-a1r-reduced.jpg) The library owns 6 copies of the 1462 Bible: one almost complete vellume copy, one copy of part 1 of the second volume, and 4 fragments, one of which belonging to the Bible Society. The vellum copy of the 1462 Bible (Inc.1.A.1.3a[3762]) is certainly one of the highlights among the books catalogued so far. It is lavishly decorated by partial borders and initials in foliate design in colours and gold which have been recently attributed by the art historian Mayumi Ikeda to an imitator of the Furst Master operating in the late 1460s or early 1470s possibly in Heidelberg. The Bible came to the library only in 1933 through a donation by Arthur William Young. Neither of the known previous owners, the unidentified Renard du Hursan or Hursau whose name appears at the end of the second volume with the date 1573, and the English Victor Albert George Child-Villiers of Osterley Park, 7th earl of Jersey, left any trace in the book.

The library owns 6 copies of the 1462 Bible: one almost complete vellume copy, one copy of part 1 of the second volume, and 4 fragments, one of which belonging to the Bible Society. The vellum copy of the 1462 Bible (Inc.1.A.1.3a[3762]) is certainly one of the highlights among the books catalogued so far. It is lavishly decorated by partial borders and initials in foliate design in colours and gold which have been recently attributed by the art historian Mayumi Ikeda to an imitator of the Furst Master operating in the late 1460s or early 1470s possibly in Heidelberg. The Bible came to the library only in 1933 through a donation by Arthur William Young. Neither of the known previous owners, the unidentified Renard du Hursan or Hursau whose name appears at the end of the second volume with the date 1573, and the English Victor Albert George Child-Villiers of Osterley Park, 7th earl of Jersey, left any trace in the book.

![Inc.3.J.1.3[3576], a1, Sarum Missal - reduced](https://inc-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Inc.3.J.1.33576-a1-Sarum-Missal-reduced.jpg)