Three Unique Caxton/Maynyal Leaves? – A post by Ed Potten

Between 1487 and 1488 Caxton commissioned the production of two liturgical books from the Parisian printer Guillaume Maynyal, both of which are rare survivals. ISTC records only one substantially-complete copy and two fragments of the 1487 Sarum Missal [ISTC im00719200 – National Trust (wanting 23ff.), Durham (3 ff.), Oxford (2 ff.)] and one substantially-complete copy and four fragments of the 1488 Sarum Legenda [ISTC il00118200 – British Library (imperfect), Cambridge UL (29 ff., Inc.2.D.1.18[2544]), Cambridge Clare (fragments), Cambridge Corpus (fragments), Paris BN (fragments)].

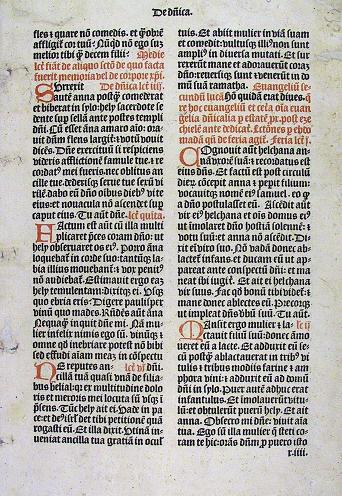

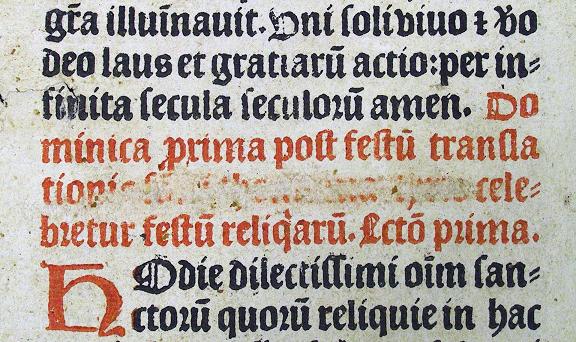

To reproduce liturgical books successfully, incunable printers needed to overcome significant typographical complications, not least the need to print in more than one colour. At the press he established in Bruges in 1473, Caxton, under the tutelage of Colard Mansion, experimented somewhat unsuccessfully with ‘one-pull’ two-colour printing. The eventual adoption of a ‘two-pull’ process overcame this problem, but liturgical printing on a large scale required a higher degree of technical proficiency than was available in the late 1480s at Caxton’s Westminster press. As a consequence the printer sought to ‘out-source’ the work. By 1487 the printing of liturgical books, some coloured, some specifically for English use, was already well established on the Continent – ISTC currently records 118 missal books and 196 breviaries printed on the Continent prior to 1488, with two breviaries specifically for Sarum use. Specialising in the production of these typographically-complex works, the printers of Venice, Basel, Louvain, Rouen and Paris cornered the market in liturgical printing and were the logical choice for the printing of English liturgical books. Caxton’s chosen partner was Guillaume Maynyal, a Parisian with proven experience of liturgical printing in red and black.

ISTC records only nine issues associated with Maynyal, surviving cumulatively in only 76 copies. These are grouped into two periods. Between March 1479/80 and September 1480 his name appears in five colophons alongside that of Ulrich Gering in books including a Psalterium Romanum and a copy of Guido de Monte Rochen’s guide for priests, Manipulus curatorum. In 1487 and 1488 he worked for Caxton, then in 1489 he issued alone two further liturgical books, a Latin Psalterium and a Manuale Carnotense. The fragments of the 1488 Legenda are the only example of Maynyal’s work in the CUL collection.

The decision to out-source to Maynyal is significant. Printing in England before 1534 was dominated by, and dependent upon, foreign tradesmen. In 1484 Richard III had introduced legislation exempting “merchant strangers” from any restrictions on either printing in England or bringing in books from abroad. The contracting-out of complex work to foreign presses and the immigration of skilled Continental printers and tradesmen became the lifeblood of the English print trade. Caxton’s employment of Maynyal is the first known example of this trend.

Set in two sizes of type, the Sarum Missal and Legenda may be seen as marking the beginnings of a transition in the typographical appearance of English books, away from styles characteristic of Flanders and Cologne, and towards type-styles imported from Paris and Rouen. Following the partnership between the two printers, Caxton purchased type from Paris, probably from Maynyal himself.

The study of any type of printed output of the fifteenth century is hampered by the quantity of material lost to researchers. Certain classes of books, however, have suffered more significant losses than others; printed liturgies are one such class. Their poor survival rate is at least partially explicable by their practical nature and the type of daily use to which they were exposed. With the exception of the most lavish, printed liturgies were working books. Often associated with chapels and chantries they saw heavy use by multiple priests on every day of the liturgical year. Not considered ‘collectable’ for their antiquity until well into the eighteenth century, these hard-used books were superseded and discarded. In England, the 1549 Act of Uniformity and its successors further explain the paucity of surviving pre-Edwardian liturgies, whilst in Catholic Europe the imposition of the Missale Romanum after 1570 had a similar effect.

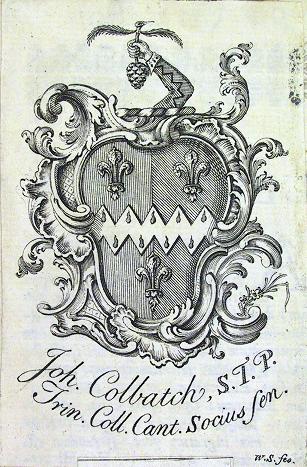

The provenance of at least some of the Cambridge fragments is traceable. One leaf bears a clearly recognisable shelfmark, Pp.1.167, indicating it was once part of the binding of a copy of the Opera of Jacques Cujas (Frankfurt: 1595) belonging to John Colbatch (1664-1748).

The leaves of the Sarum Legenda utilized by the original binder were removed and preserved when the book was rebound in 1937. There are other occasional tantalizing hints about the earlier use of the Legenda. References to Pope Gregory have been crossed through on sig. y3v and references to the translation of St. Thomas excised on sig L7r, suggesting it was in English hands in the first half of the sixteenth century. In addition, there is an intriguing Hebrew inscription on sig. y6v, which is currently being researched.

The 29 leaves which survive at Cambridge are:

Sigs. r4, v1, v8, y1, y2, y3 and y6 (conjugate), y7, y8, z1, L1 (2 copies), L2, L3, L7, L8 (2 copies), M6, N1, P4, P5, Q2, Q5, Q7, T4 (final line of both columns cropped on verso), T5 (first two lines of both columns cropped recto and verso), V3, V4 (cropped), (2)b1. There is one additional fragment, which is too small to identify.

Sigs. r4, Q2 and Q7 are almost certainly unique – they are wanting from the only surviving substantially-complete copy, that at the British Library (IB.40010), and in the absence of a definite identification of the fragments in Clare, Corpus and the BN they are at present the only known surviving examples of these three leaves. Ed Potten

Bibliography

W. Blades The biography and typography of William Caxton (London: 1882) p. 52.

P. Gaskell A new introduction to bibliography (Delaware: 1995) pp. 137-8.

L. Hellinga (ed.) Catalogue of books printed in the XVth century now in the British Library – Part XI England, (The Netherlands: 2007) p. 342, 346.

L. Hellinga ‘Fragments found in bindings and their role as evidence’ in ‘For the love of the binding’ Studies in bookbinding history presented to Mirjam Foot (London: 2000) pp. 13-33.

P. Needham ‘Caxton, William (c.1422-1491)’ in Europe 1450 to 1789 Encyclopedia of the early modern world volume 1 (New York: 2004) p.430.